About Spaces

By Ivan Pope

I have been invited to a panel on History of Cybercafes and Collaborative Space, to be held on 2nd March in Google Campus.

Yuri Pattison gave us this brief:

As part of an on-going investigation into alternative strategies for peer-to-peer information and skill sharing, discuss a growing online economy built on information sharing yet controlled through central governing bodies. Speculate on future strategies for a more democratic digital economy.

Operating out of chosen sites of co-production and working, Pattison negotiates the ethos and driving forces behind maker culture, peer-to-peer learning, skill sharing and online networks. With this work Pattison aims to stimulate a wider conversation around immaterial labour, digital economies and the political implications of technological advancement and questions how we deal with transparency.

Explore ideas of the networked society, both immaterial and physical, and the fragility of the internet, which the artist describes as ‘an architecture on the verge of collapse’

My talk here:

I’m not so good at this, but I thought it would be interesting to race through some history of the collision of physical and digital space, at least from my perspective.

My life has been a process of engaging with both the concrete and the virtual worlds, often in parallel or without realising quite how intermingled these worlds are. As a drifter, as a student, as an artist, as an entrepreneur, as a parent and as a writer, physical spaces are crucial because they function as portals to a (partly) other world. The constant switching between these two modes of space became more interesting when, at the end of the eighties, the networks were layered over the top and we all took up residence in a numinous space. It seems that we cannot separate these two worlds, that we are doomed to exist in both.

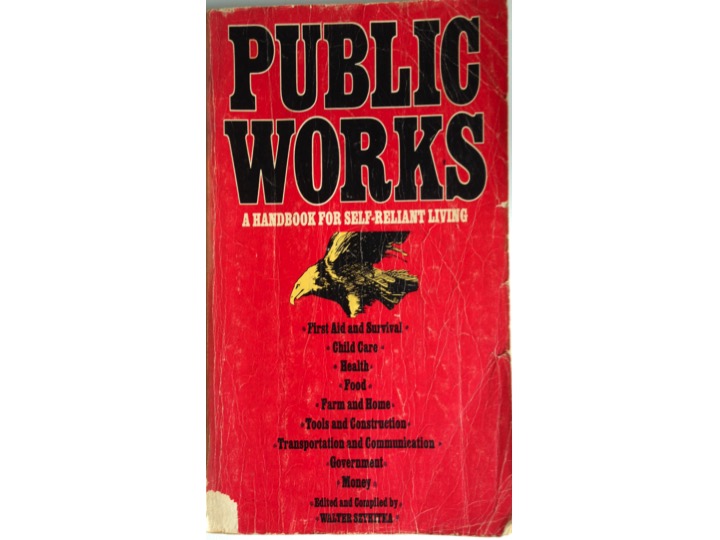

[Public Works]I think it is important and valid to examine the overlap between the networks of the historic and concrete world and those of the contemporary and digital world, otherwise we are doomed to believe we are inventing something that is, in fact, grounded in our past. Networks of knowledge have always existed and there have always been peer networks. There has always been a desire to distribute these stores of data and to build networks of like minds around them.

I’ve always thought of this book as a prototypical internet – my father brought it home for me in the Seventies from his job on a newspaper and I loved it immediately.Long before the web I would spend far too much time surfing its pages and learning about things I had no idea I was interested in. It’s over 1000 pages long, basically a compilation of government issued tracts and leaflets.

[Septic Ears]When punk came along it changed everything. It’s hard now to remember quite how cathartic this revolutionary this movement that told us we could do anything we wanted was. It took me out of school and got me writing, photographing bands and publishing zines, and opened my eyes to the nature of collaborative work, to information distribution and publishing and to the ability of creative endeavours to open almost any door. As the Desperate Bicycles put it, ‘It was easy, it was cheap, go and do it’.

[World Wide Bribery Web 1977]Tim Berners-Lee was born in 1955, probably the peak year for those who were the driving creative force behind punk and, although I won’t credit him with being a punk, he was, in 1978, working to create type-setting software for printers. The confluence of ideas and methods of their distribution, the synthesis of the virtual and the concrete, the manifestation of information networks, all come together again and again with a meshing of technology and desire. Ten years later, it was Desk Top Publishing and a new art movement that brought me into the purview of computers and networks.

As Berners-Lee said, and as Yuri bastardised, Enquire Within Upon Everything.

[Factsheet Five ]However, punk couldn’t last and, although it has become almost the defining viewpoint these days, it fizzled and died upon the Thatcherite realist doctrine of the eighties. It took the arrival of the internet, fifteen years later, for those ideas to be revived in any meaningful way.

[Anarchist front page]So I moved to London and found a whole city full of physical space, there for the taking. There still existed the remnants of the seventies counterculture, a flowering of alternative publishing modes, magazines, pamphlets, squats, communes, wholefood cafes. It was just a bit tired and layered with the new brutalist politics of Broadwater Farm and Stephen Lawrence. There was a world of the senses, of the intellect, layered on top, you just had to work hard to find it.

I wasn’t yet an artist, or hadn’t come to think of myself as an artist and of course there wasn’t yet any internet. Or computers. Or any technology. We had Walkmans and vinyl. And photocopiers. Does anyone remember the copy space at Kings Cross? A prototype of a communal media space full of photocopiers, cutting and paste up tables.

[Broadwater Farm]I moved in with some friends in what was known as short life housing, a form of legalised squatting full of students and artists and political activists, junkies and drifters. By the time I arrived there was a network of short life housing co-ops which managed properties for the council, in theory paying the rates and keeping them in good order, though the practice was generally a bit different.

This was a time when space in London was a lot looser than anyone today could imagine and this formed a subculture, a set of networks through which ideas and people moved, creating ideas and distributing them – propaganda by the deed.

But even by then the old ways were dying. Margaret Thatcher had been in power for a few years and was throwing the grand plans of Labour councils into reverse. A process called Municipilisation by which councils bought houses on the open market to convert into council houses was thrown into reverse and the liberalisation of the stock markets was bringing a flood of easy money into the city. The age of networks founded on easily available space was coming to an end.

[Freeze]I went to Goldsmiths’ and quickly learned there was another side to the post industrial wasteland. Thatcher had given the Docklands to the LDDC, a free floating avaricious organisation which lent space to the entrepreneur Damien Hirst. The rest is history. Artists had been making use of surplus London docklands since the war and probably before, and successfully too. It is often forgotten now how the early YBA successes were built to a huge degree out of empty warehouses, literally on the decaying body of industries that were over.

[Spotlight]It was out of this encounter with an aggressive and rapacious new art world that I literally discovered the networks. Writing about events around the Freeze exhibition led to the discovery of first computers and then the global networks. Having something to say led me to explore whatever technologies I could get my hands on, but being grounded in a philosophy that said Just Get Up And Do It allowed me to use these systems to find something more than the sum of the parts.

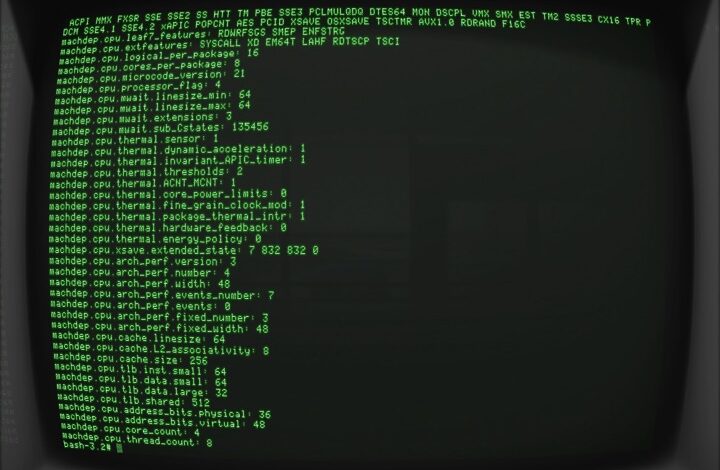

[Green screen terminal]There was no computer labs and there were no networks, but after a while I worked out that there were networks, they just needed winkling out from the system. I read an article about them and asked for a network account. After that, I was on my own with a text terminal and a magazine article as guides.

>>Story of first email<<

I looked at the screen and thought – In there, I could make work in there. There are people in there, an actual space. I didn’t think about what we would now look at as the online world with all its potential. I just literally thought I could go into this place and make some work.

The networks at this stage were a strange place, populated by a tiny cohort of users (though to me it seemed like a vast, endless, community). Alongside the academics and the military I found it was riddled with artists. The artists were already making work in this digital space, replicating networks that were familiar from mail art, sending and manipulating images using email and ftp. As always, the artists were in the lead.

[3W]I graduated in 1990 with a dissertation, The Art of the Network, and my life split into two parts and I didn’t know which one held more potential. I wanted to reconcile them without losing either side. It wasn’t very simple to work out what to do in this space. I wasn’t even sure it was a space for ages. Nobody seemed very interested in the networks whereas I wanted to evangelise them. I wasn’t very technical, I wasn’t a hacker or a coder. I got a job back at Goldsmiths’ in the old chemistry labs, now the computer department. I think I was about the ninth employee. I immediately set about exploring the networks again, and I proposed a research project to the Arts Council for which I got funded in 1991 and I built a bulletin board for artists, a dial up space called ArtNet. It was something of a failure, mainly because nobody had computers at that point, let alone artists, but I believed then that the networks would liberate us in some nefarious way. I spent the whole time encouraging people to get email, to get a computer, to get on my bulletin board. But, to be honest, it could never have worked. Nobody was there yet. This was an example of the virtual outstripping the physical.

[Loophole Cinema]I was also working by now with Loophole Cinema, an arts collective that made huge film performance installations in site specific locations. Nowadays it’s called expanded cinema. It involved mucking about in huge empty buildings and manipulating light, sound, film and audiences. I was the builder of environments and I spent a lot of time doing was trying to get Loophole to use technology. Again I was trying to fuse the two parts of my vision, the physical and the digital. Again, in this I was largely a failure, ahead of my time. The physical was still resolutely ahead of the digital.

However, while working at Goldsmiths’ (and failing to get them onto the internet), I encountered the real IP networks, the internet, for the first time. The Web was a microscopic part of the mix, but I could see immediately that we were on something like a derive, a Situationist drift through a world that I could barely envisage, but which seemed to be coming into view.

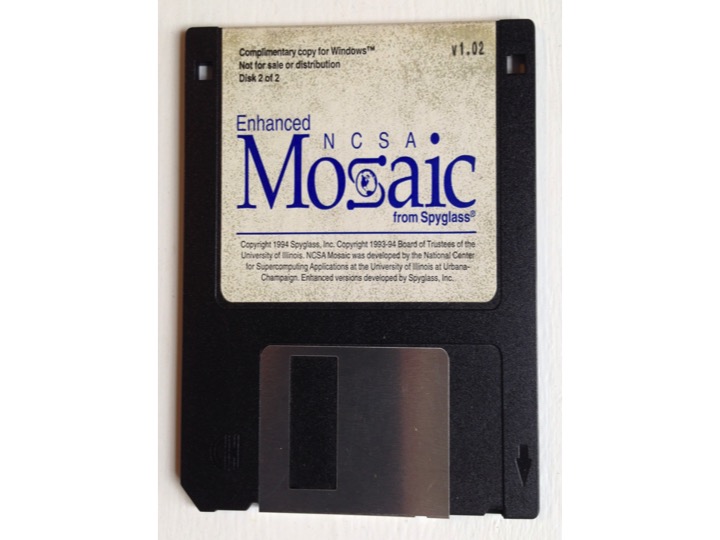

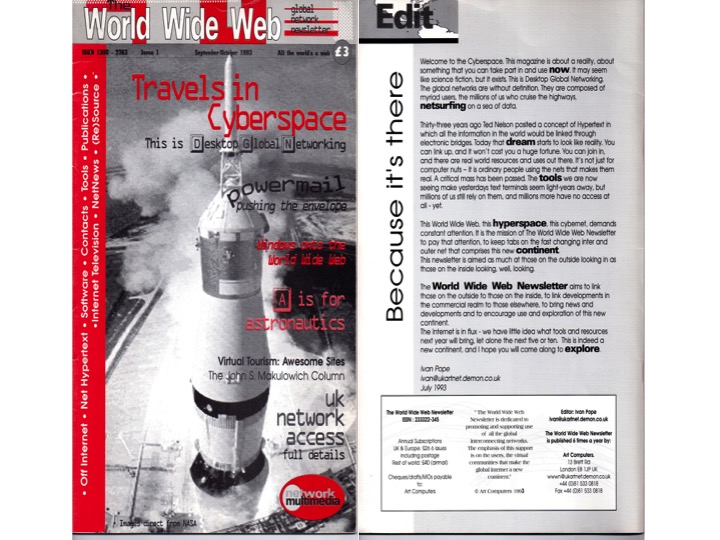

[3W mag]Following the arrival of the actual internet at home with Demon’s ‘tenner a month’ offering in the early nineties, actual real IP access was finally available, albeit via dialup modems. Emboldened by this momentous change, and inspired by the work of Tim Berners-Lee, I started a magazine called The World Wide Web Newsletter, and left my job. I wrote and designed almost the entire thing from my desk at Goldsmiths’ and my flat in Hackney and printed and published it myself. Reported in the first issue was the fact that the Web software had been placed into the public domain by CERN. To explain the Web I wrote that it was a network of computers and there were now almost one hundred servers on this network. One hundred. The moment of fusion, the big bang of the internet as we now know it. I got the first printed copies while building a vast Loophole Cinema installation in a disused steelworks in the Ruhr valley amid the debris of the German economic miracle.

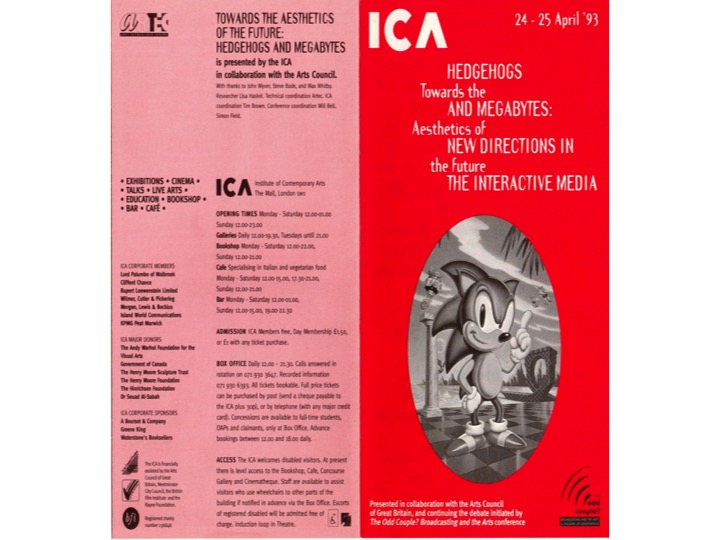

[Seduced and Abandoned]This is the conference for which I invented the Cyber cafe. The conference was a series that the ICA used to run called Towards the Aesthetics of the Future. In 1994 it was called Seduced and Abandoned: The Body in the Virtual World. I always liked that title as I had already started to flip-flop between the virtual and the physical worlds. I was constantly being seduced and then abandoned. It seemed I needed to choose one or the other, but I wanted both. I’m still in that quandary.

[.net magazine]By chance Future Publishing turned up bought 3W mag (an early example of an aqui-hire) and I went to Bath to start .net magazine. However, things were far too exciting back in London where the web was starting to get serious traction. My two lives had collided, the physical and the virtual, and it was a bit all over the place. Back in London the magazine got me a lot of attention and I was starting to see how the internet had a mesmeric effect on people who encountered it, as if once they had looked into the void they could not look away again. I hadn’t seen anything like that ever so I decided that I had to pick a horse and stick with it.

[Webmedia]I started Webmedia with Steve Bowbrick. After looking around Shoreditch we settled into the basement of the real cyber cafe, and we settled happily into their basement.

I did this, of course, by dreaming up a new industry, starting a company called Webmedia and renting a physical workspace, the basement of Cyberia. I was no longer quite an artist, I was learning to be an entrepreneur, largely by accident. To strt with I invented some slogans for the new world. Let a thousand flowers bloom. Beneath the pavement, the internet. It’s the internet, stupid.

[.net Cyberia]I wrote about my new landlords, of course. This was a new sort of space, upstairs and downstairs creativity raged, in the cafe everyone met everyone else to tell them about the newest new thing. Who were the artists? It didn’t seem to matter any more. At this point my greatest artwork so far was taking shape.

[Cyberia]Cyberia was for a brief flowering moment the centre of an entire universe as people became sucked in from all around the world to see this new thing. It became a crazy real world space all jumbled up with the online space, so much so that at times nobody knew which world they were in. I believe that in this moment some of the best approaches to the digital world were invented or conceptualised, though most were seeds which would take decades to flower.

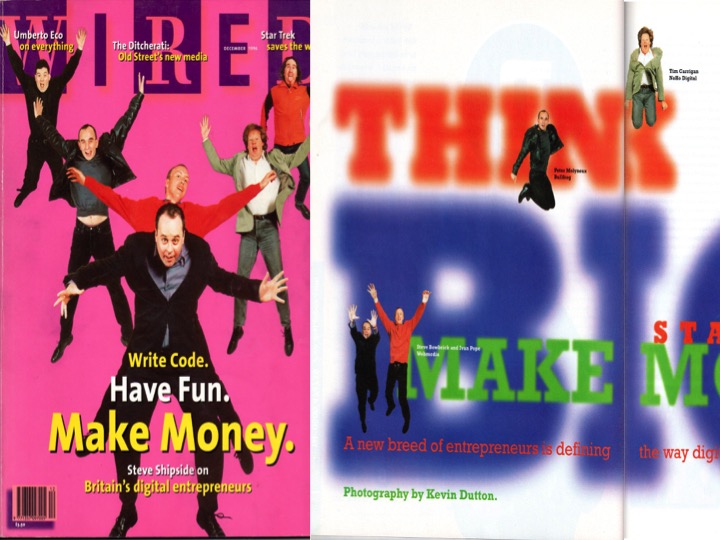

[Wired]Someone put us on the cover of Wired magazine. UK edition. Interestingly this issue’s other cover story was about Shoreditch – the Ditcherti. Wired closed down soon afterwards but Shoreditch steamed on regardless.

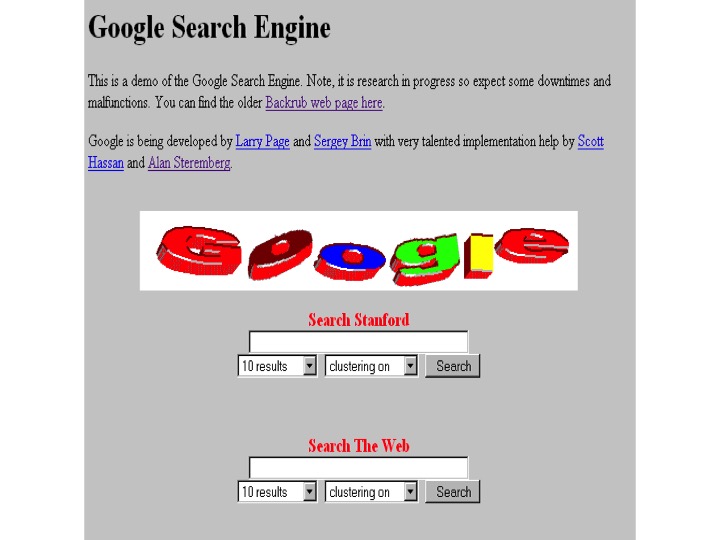

[ Google ]1997

Then a strange thing happened. I found the space that was the most lucrative and the least creative, but also the space that gave me the deepest insight into how online was sucking the physical world into a new reality. Without going into details, I invented the domain name registration industry and started a company called NetNames. This led me deeply into the domain name wars as a global struggle broke out around the issue of who controlled the infrastructure of the internet. Domain names, specifically .com, became hugely valuable properties and we gathered in various international organisations to discuss how to manage them for the future. It was at a meeting in the hallowed halls of the World Trade Organisation in Geneva that I had a vision of governance of the root servers, the holy grail of internet traffic, lifting off from the planet and ending up residing somewhere that was in no country.

After that meeting I got on a plane back to London and landed to find that Tony Blair had been elected with a landslide majority. Normal life recommenced.

[FabLab]Now, as if by magic, a new old thing arising in the world, a thing that seemed to meld everything I’d ever been interested in in perfect synthesis. I started to read about this experiment to build a 3D printer that could replicate itself – the RepRap project.

Then I found out about a project to build public spaces for making things with digital tools – the FabLab project.

Then I started to read about a network of spaces that were available for shared workspace, most with their own unique approach to environment and working life. That is the Coworking movement.

It seemed to me that everything I’d ever been interested in was arriving all at the same time, and from an unexpected source.

Artists studios

Coworking

Digital tools

Hardware

Networks