Who owns your face? – biometrics in your town

Live Facial Recognition is being deployed in many cities world-wide, but who really owns your face?

Facial recognition tech is getting more accessible by the day, with urban applications varying from the wacky to the scary. Amazon ReKognition software means anyone can add Facial Recognition to their monitoring systems – the barrier of entry is very low.

New applications emerging during Covid19 are showing the kinder site of Facial Recognition with tools that save lives, improve face mask compliance or protect children in schools.

Cybersalon invited international biometric and AI experts on 17th November 2020 to shed new light on ownership of personal biometric data and it’s use in the cities. Why is this tech suddenly exploding on our streets?

Introduction: Strain on the Train

7 people had their images captured on Kings Cross train station (London) and passed from Metropolitan police to Kings Cross owners in a secret deal that only came to light in 2019. Two ‘smart cameras’ were installed at this busy London train station back in 2016. Catching a train from Kings Cross would lead you to having your face captured and analysed in real time against Met criminal list photo database.

Thousands of people had their faces captured and pattern-matched by Artificial Intelligence face recognition tool during 2 years of AI cameras operating at Kings Cross with no permission, safeguards or procedure. King’s Cross is owned by property developer Argent and BT Pensioners, the latter has not been consulted on using their money on secret surveillance of commuters.

There was no sign of follow up, no records were kept regarding how successful the matching actually was in practice and if any of the seven people were actually recognised, according to Metropolitan report on King’s Cross deployment.

Despite public outcry, new deal has been reached on data-sharing agreement between King’s Cross (no longer a public space) and Met police in London.

However, Biometric Commissioner for UK has not supported the agreements and went on record explaining he did not back the use of LFR tech.

Prof Paul Wiles noted that he argued for proper governance of biometric surveillance, and recommended that parliament should decide on it, not the police.

Ignoring his recommendations, police has gone ahead with extensive testing in 10 areas of London, with fining a man £90 pounds for declining to be scanned by facial recognition camera in other London location. So called ‘watchlists’ of faces have been created and more than 20mln photos of faces are now contained in police databases. One of the controversies was that one of the ‘identified’ teenage boys had already been thru the criminal justice system. There are also issues with actual technical accuracy of face matching and wide open room for errors. MP Norman Lamb noted that it is ‘unjustifiable to treat facial recognition data differently to DNA or fingerprint or other biometric data”.

US cities take a stand

In US the misuse of facial recognition led to a ban in San Francisco, led by Aaron Pesking, the city supervisor who said that ‘it sent a particularly strong message to the nation, coming from a city transformed by tech’. Other cities followed, although the a Bill passed in the State Legislature only gone as far as ban on commercial use and let it unclear what is the legal framework for the use by police

Matt Cagle, a lawyer from ACLU (Cali) noted that this tech ‘provides government with unprecendented power to track people going about their daily lives. It is incompatible with a healthy democracy”

Black Lives Matter movement has speeded up the rejection of LFR tech in more cities, with Portland (Oregon) passing wide city ban in Sep 2020. Boston, Oakland also passed moratoriums, on the grounds that flaws in these systems can lead to false positives with serious consequences. “Nobody should have something as private as their face photographed, stored and sold to third parties for profit’ commented Jo Ann Hardesty, City Council Commissioner leading Portland ban.

However, most cities are busy deplying so called ‘smart lamps’ where Live Facial Recognition is embedded in streetlamps cameras – initially sold as help with parking, but day comes after night, ended up as urban surveillance tool.

Canada LFR shock

In November 2020, 5 mln shoppers’ images were collected at malls across Canada by Cadillac Fairview. The company embedded unlawfully cameras inside digital information kiosks at 12 large shopping malls across the country with no consultation or legal framework.

This software took face data and converted the information to compile demographic info about mall visitors. Daniel Therrien, Privacy Commissioner of Canada found out that supplier had no clear answer to the question why the images where collected, only passing on the comment that ‘the person responsible for programming the code no longer worked for the company”.

We have arrived at pure Wild West of Live Facial Recognition tech and vendors’ following Google’s build things first, asking permission after.

Facial Recognition technology is getting cheap, as data storage and AI image processing costs fall thru the floor. This tech is ubiquitous and tempting to every retailer and police alike- both groups are under financial pressures, both seeking new shiny tools to automate their work on the cheap, be it marketing or urban policing.

Governments to the rescue?

Discussion summary:

Cybersalon panellist, Derek Alton, Canadian consultant for systems in tech and society (Newspeak House Fellow) noted during Cybersalon discussions that at this point it is vital to re-build the trust in urban infrastructure and that this needs to be underpinned by trust in government.

“If we don’t’ trust the government, who do we trust? Certainly not the commercial companies”.

He also notes that LFR is a powerful tool, and it is essential to examine the business models behind LFR. We need to consider who benefits from LFR, who gets technical advantage, and mitigate it by appropriate governance”.

Urban face watchlists and how do you get off them?

Where Live Facial Recognition is really highly risky and can really impact your travel plans if there is false positive result during LFR use at the airports.

Edward Hasbrouck (US travel surveillance expert) points out that airports can be owned by governments, commercial entities or a mixture of both

“In such complex ownership structure, passangers can’t tell if their faces are recorded by government or private entity and how the data will be used”

Edward also points out that use of facial recognition during Covid is particularly suspect as it actually needs the passanger to take off their mask – something that may be a risk to them catching the disease.

Worth noting that photos are added to Permanent Travel Dossier and although photo is not always kept, the logs are kept and can be used to back-engineer identity. This includes travel points, time stamps of movement within airport. If your name ends up on No Fly List, it may result in a wide range of actions, from Air Marshall sitting next to you to ban on travel on this or /and other routes.

In EU, the system is based on Positive Control, which means you are not allowed to travel until government permits you to and permissions have to be given ahead of the journey. The default set up is a negative, not something people realise.

“Facial recognition enables granular level of control, with no need for checkpoints on the street” says Edward.

But who has this control vary in different countries, as faces can be gathered by the government or private airport owners, adding to the confusion and making recourse from errors extremely difficult.

Who needs to know about LFR?

The answer is that everyone needs to know but particularly young people, whose actions at pre-teen age can be caught on cameras and follow them with repercussions long into their adult life.

Stephanie Hare (@hare_Brain) , author of the upcoming book “Technology Ethics” aims to make ordinary people and particularly young people aware of their urban surveillance risks.

“Young people are often not aware that body data can be taken” notes Stephanie.

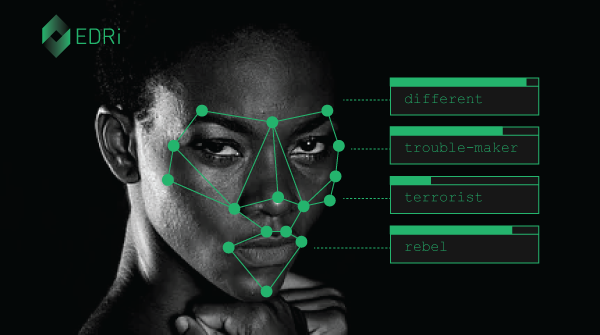

She points out that women of colour are at extra risk of false positives as the training sets appear to be inadequate to ensure high accuracy of LFR systems

Research by MIT found out that top facial-recognition software was inferior at correctly identifying the gender of women and people of colour than at classifying male, white faces.

Young people need to understand this, be aware that algorithm is only as good as the training material, and biases can easily creep up into even the most carefully constructed data set.

However, Stephanie is also careful to note that society’s acceptance of LFR should not be solely led by technical accuracy debate:

“It’s use in a public space is changing the nature of the personal privacy and the way we interact with cities. For this reason, the debate about acceptance needs to be ethical and not just technical”.

From Algos to Alcohol

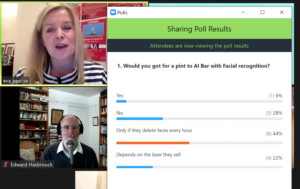

It is not just doom and gloom with LFR. AI in facial recognition has also found good uses, and AI-bar is one of those. John Whylie from DataSparq has noted that queueing in crowded the bar to get a beer is often a harrowing experience. To bring order to chaos he has designed a camera that captures faces of the punters, counts who came first and second, and project this with numbers above customers’ heads on the screen above the bar and on bar tender’s dashboard. In that way, bartender can see exactly who should be served next, avoiding you having to push and shove just to catch the eye of the busy barman.

John notes that the photos are not gathered, the purpose is to eliminate stress and not to add to it. We have run a short poll during Cybersalon event asking if people would mind if the queue management system was numbering their faces.

The typical answer was that people found this acceptable, as long as the faces were deleted after 15minutes, thus avoiding the risk of the data leaking out and causing problems later.

Please wear a mask

Gus Fraser from Visual Monitoring noted that shop assistants were often to scared to ask customers to wear a mask. He designed Face Mask alert system based on Raspberry PI and Tencent Flow training model. The device, of the size of 2 match boxes, can be fixed by the entrance to the store, school or hospital, and recognised if the person entering is wearing a mask.

The system uses face recognition as based to tell if the mask is present or absent, but otherwise it has no interest or need to keep the face data. The faces can potentially be used for footfall counting but it would only count numbers ‘With Masks’ and “Without Masks’ as it is not geared to analyse faces. In addition the analytics of faces from limited data points above the mask although possible, can’t have it’s accuracy can’t be guaranteed, as noted by software developer Simon Sarginson (Cybersalon.org).

The question was raised by Dan Stapleton (Network Rail innovation team) that in the absence of logs from Face Recognition, it would be hard to examine if the ethnic or gender recognition bias was absent from the system. Logs must be present and auditable.

How did AI landed on face recognition ?

History of AI has been originally focused on philosophy and modelling of languages. Satinder Gill (Cambridge University), editor of long-running Journal of Artifical Intelligence and Society noted that it was the shift away from simulations to ‘brute force’ of simple patterns recognition that has opened up AI to speech recognition and face recognition.

In fact one could argue, that those successes in speech and face recognition are not successes of us understanding better human intelligence and therefore being able to create Artificial Intelligence. It is only the low cost of storing huge amount of data, like speech samples or faces, and fast falling cost of data processing that has brought AI from the academic hobby to being useful.

But we should reflect on appropriateness of use of the term ‘intelligence’ in such contexts.

Satinder agreed with previous speakers raising issues with technical accuracy of algorithms and mentioned that women of colour are at extra risk of false positives as the training sets appear to be inadequate to ensure high accuracy of LFR systems in those specific populations.

Joy Buolamwini at MIT found out that top facial-recognition software was inferior at correctly identifying the gender of women and people of colour than at classifying male, white faces. Error rate on facial recognition was 28% higher for women and 45% for darker skin recognition. Clearly not an acceptable level for a reliable tool in urban surveillance.

Another new risk of Facial Recognition is use of the recorded faces in creation of Deep Fakes- as noted by Derek Alton.

Gus Fraser’s response was that it is possible to create an AI image recognition system to reveal Deep Fakes and alert if the faces are not real.

Joanna Bryson (Hertie University, prof of Technology Ethics) brought up the glasses that were invented to confuse LFR and make everyone look like Brad Pitt. If we can’t believe our own eyes, it raises very serious questions about the trust in any images shared in public media.

How do you build trust in the Age of Deep Fakes – Recommendations

Joanna Bryson (Hertier University, Berlin) urged that ‘we are facing a challenge of losing trust in technology, we need to slow down and rebuilt Governance”.

We are not going to go back on technology, the only way is forward and regulation.

She argues for :

“weakening digital giants with Digital Tax as well as putting more effort to build systems to protect our data on government platforms, on systems equipped with values that will be akin to our values”.

Wendy Grossman (NetWars) commented that “we have demonstrably untrustworthy leaders in number of governments”, noting crisis of trust not only in technical suppliers but the government.

Derek Alton (Digital Canada) pointed out 3 ways of trust building –

“give people control (to opt in or out), built useful tools that make life easier and secure trust over period of time, and thirdly associate tech with things people trust, recommendation by more informed family member or trusted high profile person like a well-loved celebrity”.

Edward Brockhouse recommended that

“trust tools need to be stronger, firstly use of immutable logs, second, use of mandatory government audits , thirdly use of Judicial Review”.

He also insists we should make a distinction between algorithms that identify faces/people, or actions. Both of those come with their own risks.

His advice is that we, as civic society,

“need to push and create technology accountability outside of tech, make tech accountable to citizenry”.

Eva Pascoe noted that :

“Under age festival goers to Download Festival in 2018 had their faces recorded with no permission or opt in, and shared with local police despite no disturbance or behaviour issues registered on the grounds of festival”.

We don’t want to result to Dazzle Club-like actions of having to paint your face in abstract lines to confuse Facial Recognition tech

To stop use of Facial Recognition in our cities, we need to redefine use of public space or space that people think is public. EU has accepted 2017 that Biometrics are Personal Data, should come under GDPR. But it has not been challenged and UK leaving EU leaves UK citizens at a particularly risky and vulnerable situation.

While recognising that Facial Recognition can bring positive social use like Face Mask use monitoring or pub queue control, the risks of having FR in public space is too high to let it go unregulated.

We must press MPs to force clear legislation, including the requirement for immutable logs, governmental audits, expert audits of log archive while recognising that technology is becoming cheaper by the day and more cities will deploy it without due regulation.