Track and trace or duck and dive – Covid19 surveillance apps

Covid19 has brought us pain and suffering but also a huge number of new words and phrases. One of them is Syndromic Surveillance. It’s a new one for me, although this term has been around for a few years now, as bio-warfare anti-terror preparedness tech kit launched it the wake of 9/11. Recent events have put it under the spotlight once again. The term refers to methods relying on detection of individual and community health indicators that are noticeable before confirmed GP diagnoses are made. The practice of electronically monitoring and reporting real-time medical data to proactively identify unusual disease patterns, right off the start has hit the conflict between public health and personal privacy. Originally developed for detection of covert bioterrorist attack, it could be used against anthrax (ncbi.nim.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC353021/, detecting influenza like illness as an early warning.

Inevitably, syndromic surveillance is now making its way rapidly into our everyday language during Corona time. We want to make the invisible visible, finding ways to force the virus the surface, to show us it’s deadly footprint. Syndromic Surveillance is being deployed in the fight against coronavirus using Google-Apple (and other) combined technical super-surveillance machinery, aggregating geolocation data from mobile phones, cell towers, CCTV and other currently existing spy tech.

The need to use syndromic surveillance to detect movements and track-and-trace to log contacts of infected individuals is legitimate as we need all hands to the deck on this biggest health crisis in over a hundred years. Governments are scrambling to find weapons that can speed up the ability to open our economies. It is a race against time and no doubt our individual privacy will be pitted against our ability to get people and society back to work.

A number of countries like Singapore and South Korea have already introduced some format of syndromic surveillance to map the spread of the virus and monitor ‘social distancing’. Google and Apple have already had the bright idea of developing ‘track-and-trace’ apps where governments would not have access to specific individual’s locations.

Both companies insist that the user will be required to opt-in and data would be held only till the end of the quarantine period, something hard to take at face value after Google Health’s recent record of illegally obtaining real-time medical admissions data from UK top hospitals in 2015.

Facebook is already providing health researchers and non-government organisations in some countries with anonymised data to help disease prevention efforts, so expanding this monitoring to Covid-19 would be a quick win according to the company.

But does track-and-trace using geolocation data from our phones actually work?

There are 6 problems to examine before we lurch into tech-led-saviour-miracle-cures territory.

- Adoption Rates

The first is adoption rates challenge. Since Apple, Google and governments seem to insist this will be an opt-in tool, we need to understand how many people are likely to download the apps.

In practice, it will only work if at least 80% of people get the app onto their mobile.

The evidence for such enthusiasm is poor: Singapore, which deployed this technique in an app called Trace Together early on in the pandemic, had only 13% of adoption rate. This is surprisingly low, for a country where surveillance is prevalent and the population has been trained to accept it without objections.

The likelihood of this download by privacy-sensitive Europeans or Americans must be lower than Singaporeans. With such big gaps in data, even predictive analytics are going to be worthless.

- Accessibility

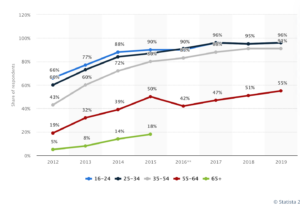

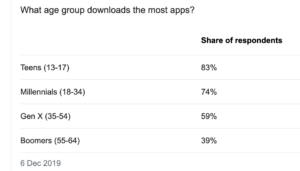

The second issue is accessibility. Even in UK, a fairly pro-mobile country, 96% of under 24s are glued to their mobiles 24/7. However, as noted by Statista, only 57% of over 55 year olds have smartphone phones and even those are mainly used for phone calls. Of course the government could make mobile phone ownership mandatory, issuing Free Phone For All Corbyn-like directive, forcing mobile phone providers to supply the 43% of 55 year olds who don’t have a phone to acquire one. But that will take a long time, plus add time required to teach the newbies how to use it.

To make matters worse, of the people in the 55+ category, the portion of them who actually have mobile phones and then proactively download apps is 39% (this is US data, with a lot lower numbers for UK). Covid19 strikes older people with higher frequency and worse mortality, so it hardly makes sense to latch on to the mobile app-based tool that only young, relatively Covid-19-proof people are going to download.

- Lack of precision

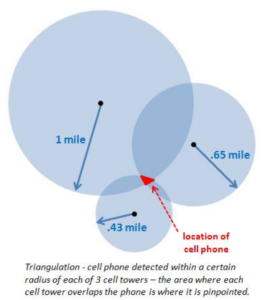

Third problem is a technical issue as telecommunication firms have cell towers data and are happy to give it to the government, but those give highly imprecise data. The granularity would not be good enough to determine precise location if the person was staying in the house or stepped out to the other site of the street and out of their allocated quarantine zone. It tends to be accurate within a street or a block, ¾ of square mile but not much more than that.

Using Bluetooth is not plain sailing either, as it will send a ping regardless if the person is half a meter or 10 meters apart from another phone. It is all very well to use geolocation for an overview of population movements, something that we have used extensively for footfall research for High Street Revival projects, but in practice, for precise tracking it would create far too many false positives to be very useful.

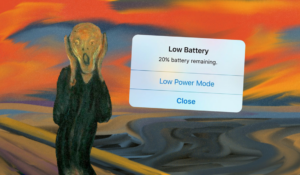

- Battery limitations

Forth issue is battery time – we struggle with it anyway, with my Airplane Mode on as a default to prevent getting stuck. Bluetooth, despite not as bad battery-wise as some people think, its still is a power sapping tool. It would be quite a commitment for the general public to have it on all the time, particularly as it would have to work many times harder, passing by other devices with newly added Bluetooth on. We could learn to manage our batteries better, but it would be a behaviour change for many as most of us are already struggling to get through the day on a single charge.

Even if Bluetooth On was made mandatory by the government, the reality is that the phones will run out of juice half-way through the day, rendering it useless for any comprehensive syndromic surveillance as people tend to move around in the evenings after work, by which time your phone would be dead unless everyone gets a free monster portable charger (a good idea but somewhat unlikely).

- Cybersecurity

The fifith issue is the problem of cybersecurity if the phone is being used for work as Bluetooth is not secure. Bluejacking, bluesnafring or bluebugging are daily threats to all of us who use smartphones for business.

Corporates don’t even like Zoom videoconferencing and their invasive recording habits, so they would not take well to the company phone being tracked, with the risk of cybersecurity if the data leaks or falls into competitor’s hands. In reality, we would have to carry two phones, one for work and one personal with the Track-And-Trace app on, which would cut the acceptance rate by half amongst professionals.

- Avoiding testing

Last, but most important issue is the perceived negative risk by the individual tested and being tracked and therefore their willingness to download the up. South Korea used a combination of cell-phone location data, CCTV and credit -card records to monitor people’s movements. When a person tested as positive, a whole haul of data was released including name, address, gender, credit card history and a full log of goings and comings from local shops. Even visiting a toilet or a love motel room is being noted, as well as extra visual information, for example if the person wore a mask. This level of details led of course to a rise in ‘armchair detectives’ harassing and exposing neighbours for minor departures from the rules. Some of the attacks were physical, it also created the atmosphere of mistrust, where many citizens refused to get tested, clearly the opposite of government’s intentions.

In fact, as people started ducking-and-diving and leaving the phone at home, or sharing phone with non-corona members of the family, South Korean government had to switch to wrist-bands to force the use. No doubt it will take enterprising Koreans a few days more to figure out how to duck this one, as nobody wants to get doxed or lynched by a neighbour going mental after too many weeks of lockdown.

What next?

The bottom line is that governments are hollowing out our hard-fought personal privacy despite the fact that much of the tech used for track-and-trace is ineffective or downright harmful as it puts people off testing like in South Korea.

The truth is that the track-and-trace apps are a diversion for the press riding on ‘there is an app for that’ syndrome of wishful thinking that has pestered our techno-optimistic Wired-reading governments for over a decade.

Syndromic surveillance and track-and-trace apps may be a small part of the solution, but short of inserting a chip into the body of everyone on the planet, the real solution is the expensive, analogue and technically unexciting mass scale testing for live cases as well for antibodies to establish who had it.

Anything else is just a dead cat on the dining room table.