Hashtag Activism, book review: A sign of the times

By Wendy M Grossman for ZDNet UK Book Reviews |

This book explores how new movements for social change take shape on Twitter, facilitated by the humble hashtag.

Last year, an inveterate internet observer called 2010 “peak cyber utopia”. That was the year Western social media users basked smugly in the belief that their technology had liberated numerous Arab countries from oppressive governments. Since then, we’ve learned that social media was only one of many tools, not a cause, watched Western democracies undermine their own democratic institutions, and come to realise that actually the internet can’t do everything.

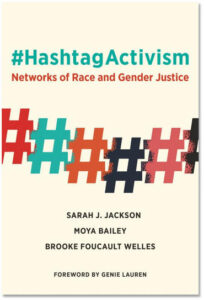

And yet. It’s one of the peculiarities of Twitter (in particular) and other social media that new movements can take shape in full public view while entirely escaping the notice of those whose bubbles don’t intersect them. In Hashtag Activism, Sarah J. Jackson, an associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School, feminist scholar and ‘misogynoir’ coiner Moya Bailey, and Northeastern University associate professor Brooke Foucault Welles, tell the stories of a number of these movements, beginning in 2009.

Theirs is a rare approach these days; these are the first authors in a long time who aren’t focusing on platform abuse. Their index has no entries for trolls, abuse, or bots.

On Twitter, hashtags — literally, the # sign in front of a word — were the brainchild of user Chris Messina, not a feature built in by the site’s creators. Hashtags provide a combination of search term and filter; entering one into Twitter’s built-in search engine produces a live feed of everything anyone’s posting using that hashtag. People use it to share comments about conferences they’re attending, update breaking news, discuss current trends, or, as in the cases these authors discuss, build evidence and a social movement, as they did during Occupy and much more since. Although the authors primarily talk about Twitter, they acknowledge that other social media — chiefly Facebook — are equally important.

Access all areas

They begin by observing that social media affords racial minorities, women, transgender people, and “others aligned with justice and feminist causes” new access that was not available via traditional media. They then go into detail in six chapters featuring the following hashtags: #YesAllWomen, #MeToo, #FastTailedGirls, #YouOKSis, #SayHerName, #GirlsLikeUs, #OscarGrant, #TrayvonMartin, #Ferguson, #FalconHeights, #AllMenCan, and #WhiteWhileCriming.

At least some of these ought to be familiar to anyone who follows the news in mainstream media. Others may be unfamiliar, particularly to a British audience. I had not, for example, encountered #FastTailedGirls or #YouOKSis, which were used to build knowledge of black feminism. Nor had I seen #GirlsLikeUs, which the authors use as an example of community building and advocacy, in this case for transgender women.

Finally, #AllMenCan and #WhiteWhileCriming examine the way offers of allyship can turn into appropriation. In their example, what began as white men offering to join in opposing discriminatory policing by providing examples of times when they were let off lightly for infractions for which their non-white counterparts would have been more severely punished, turned into a performance of privilege.

The authors do not suggest that online organising is enough by itself to effect real social change. But, they conclude, online matters. “Peak cyber utopia” may have to wait.