Three Lockdowns and a case of home-brew vodka

The UK pandemic lockdown is the first lockdown in Britain in living memory. But for many UK residents like me, brought up in Eastern Europe in the 70ties , this is the third lockdown in our lifetime.

My first was in Poland, 1981. The Solidarity workers’ movement that had emerged as a leading opponent of communist regime was gathering force. In response, the Kremlin started amassing Russian troops by the eastern Polish border to intervene. The situation looked increasingly grim and looking for a lesser-evil solution, the ruling Communist Party HQ decided to do the dirty themselves, and overnight imposed overnight martial law on the whole country from the Baltic Sea to the Tatra mountains.

We had no time to prepare. One night our one TV channel, a propaganda mouthpiece for the generals who ran the government, just went blank. The next morning, we woke up to sirens and the top general of Polish Communist Army, General Jaruzelski proclaiming on TV that we were prohibited from leaving the house after 6pm, with a country-wide curfew and full restrictions on any public gatherings. Only churches were exempt, a major oversight as that is where Solidarity continued their opposition, building the basis for the change of regime under the disguise of a Catholic mass.

I was barely 17, involved in Solidarity mostly as a courier taking photocopied leaflets to other underground groups so they could continue self-organising in the struggle against communist regime.

Schools and offices still functioned. People had to work (if the kind of work people did in Poland under communism could actually be called work), as the Polish economy was already on its last legs, with huge food shortages across the country. But the atmosphere was heavy, particularly felt by young people as we were preparing for A-levels. One of my subjects was history and predictably, the propaganda flowing from TV and radio was powered by attempts to subvert Polish history curriculum. However, our brave teachers were not to be discouraged and in my Lyceum history teaching stayed as close to the truth as possible under the circumstances. We stayed home listening to Breakfast in America album by Supertrump, dreaming about escaping from this nightmare. “Take the long way home” song from that album was particularly apt as during martial law we often had to stay at friends for the night as walking the streets after curfew would result in arrest.

The first immediate effect was a significant fall in road accidents and general crime. Poland had shockingly high road accident numbers as horse-drawn carts, buses, and (increasingly) private cars all jostled for space on narrow, damaged, mostly pre-war roads. Once the lockdown took effect, although people used the streets during the day, there were fewer deliveries because food and drink venues were closed. The evening curfew meant no drinking and driving, and no walking back in the middle of the street after a heavy vodka session, so fewer opportunities for car crashes.

The UK is already seeing a drop of about 7,000 car crashes in the few weeks since shelter-in-place began. There’s been fast growth in cyclists, with even elderly ladies getting back in the saddle, often after many years (Brompton bycicles has reported 15% growth since the lockdown began), because cycling is now safe.

The biggest similarity to the Polish martial law lockdown is food shortages. In Poland that was nothing new, as the Communist Party’s beloved command-and-control economy was anything but controlled and cracking fast, unable to “command” enough staples for everyone. So we already had rationing: paper coupons per family for almost everything from nylon tights, cigarettes, sugar, soap, and, most importantly, meat and vodka. The coupons were traded on the black market, with value depending on who needed what most. With three women in my family, all semi-vegetarians living on a diet of homemade spinach dumplings and potato pancakes with kefir, we exchanged meat coupons for extra pair of tights. Oskar Lange, the father of market socialism, would have approved of this little oasis of “free market”.

For others, the allocated vodka coupons were just never enough. True to form, about a month after martial law was introduced, many households had set up home-made vodka manufacturing. In fact, many of those home-brew spirits were much better and safer to drink than the officially distributed, heavily diluted, state-made vodka sold in Sklep Panstwowy.

I am fully expecting my friends and colleagues in London to start home-based manufacture of toilet paper – see www.askaPrepper.com/homemade-substitutes-toilet/paper/.

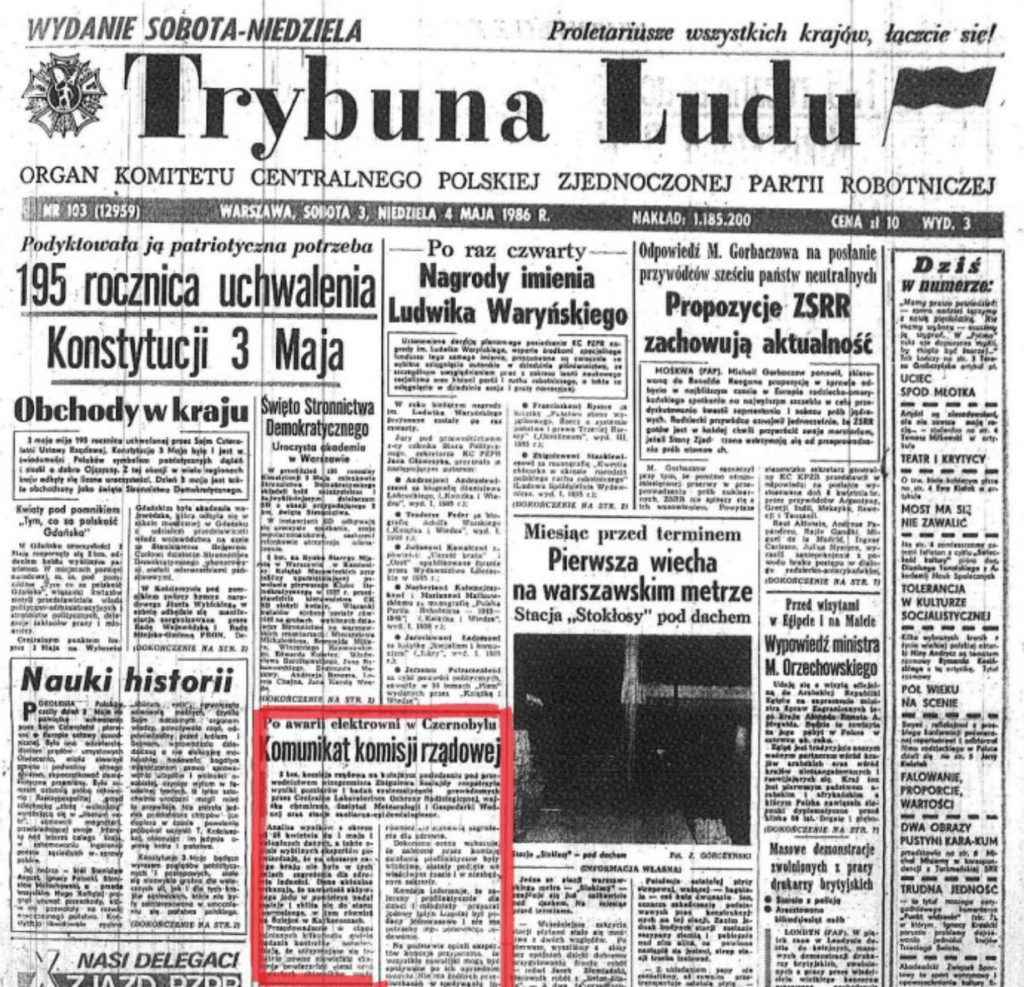

Toilet paper was not even on the list of rationed goods in Poland; we were well-trained to use newspaper, as that was all communist propaganda “news” was actually good for. Official toilet paper existed, but it was so awful that in comparison, a well-squashed Tribuna Ludu (the Party’s propaganda newspaper) was preferable.

Not all of this was grim, It was also a deeply bonding and spiritual time, just as clapping together on the streets for NHS heroes is a heart-warming bonding experience. We sang from the balconies on New Year’s “Free Poland will always overcome” and other patriotic songs. It was dangerous but it was also deeply formative for us younger people, who understood that free Poland was not this communist dictatorship version of Poland.

But martial law was also dangerous. There were deaths and thousands of arrests, mostly of Solidarity activists who later spent many months in internship camps. For young people, it was less restrictive than it looked, mostly due to the architecture of Polish housing. Underneath our tall, ten-storeys-plus blocks of flats, with their six to ten staircases, each with its own entrance, were long basement corridors connecting the blocks. Although it was dangerous and risky to leave the house in the evening, as long as you had friends or work colleagues in your block of flats, a quick run by the corridor connected you with hundreds of people. We partied, drinking home-brew vodka, with sausages smuggled in from Grandma’s house in the countryside, with delicious pickled cabbage with cumin and Baltic herring in apple vinegar, all components that worked work well for Poles in numerous earlier lockdowns and curfews during WW1 and WW2.

Although curfews and lockdowns were originally invented to stop spreading diseases in the time of the bubonic plague (“quarantine” derives from the 40 days sailors from the Middle East had to spend on an isolation island before mooring in Venice), eventually they also became a popular tool of choice for governments fighting the spread of ideas. The original ancient Greek meaning of “epidemic” incorporated anything spreading among people, including ideas. For pre-digital authoritarian governments quarantine at home meant slowing down dangerous ideas, revolutionary thoughts or even just general discontent with whoever happened to be ruling the place. This was the focus of our martial law curfew: to stop the spread of the Polish freedom movement that was challenging communist dictatorships across all Eastern European countries. Because of basement corridors and churches, it did not work to stop the frenetic discussions about the future shape of Free Poland. The lockdown ended after 18 months because it was unsustainable economically and socially. A few years later, in 1989, democracy returned to Poland.

My second lockdown was more similar to our current predicament. Early on 26 April 1986, the Chernobyl nuclear power station exploded, spitting out a killer radioactive cloud that eventually destroyed millions of lifestock, plants and caused thousands of cases of leukaemia and thyroid cancer damaging that entire generation of Ukrainian children. The Russian Communist Party, true to form, prioritised PR over health and attempted to cover up the disaster, releasing no official information until 30 April. In Poland, we knew nothing until four days after the explosion blew out the reactor. By coincidence, my flatmate was a nuclear physics student who had a Geiger counter in his lab. On the morning of the 26th the counter zoomed to extreme heights and stayed there, alarming everyone in Warsaw’s Nuclear Institute.

Despite the lack of official communication from Russia, physicists quickly figured out that there must have been a large-scale nuclear catastrophe somewhere near enough for the cloud to reach Warsaw. Chernobyl’s nuclear power station was the only candidate that fit.

We knew what to do, as we all had drills in High School how to respond to nuclear disaster: hide at home, close the windows, enact the protocol we now call “shelter in place”, and admit no fresh air. With no mobile phones and few landlines, the responsibility fell on lucky phone owners to call as many people as they could to alert them.

Then, as now, it was difficult to convey to people the degree of threat from the invisible enemy. Our friends were doubtful of the Geiger counter’s accuracy and suggested we were reading too many novels by Ursula K. Le Guin. In the general thinking, the Russians were smart physicists and were the first to send a spacecraft into orbit; surely their science was good enough not to cock up a nuclear power station management.

With no smartphones and no cameras, we could not circulate the Geiger counter photo showing its alarming measure. Our friends had to take our word for it. However, eventually people got the message and we engineered a massive stay-at- home, self-isolation lockdown while both Polish and Russian authorities were still denying the scale of the disaster.

In this self-initiated lockdown, again we had no warning and no time to prepare or get supplies. Whatever you had in the fridge, basement, or larder, was safe, and that was the only product that was safe. Radioactive fallout affects vegetables, milk and most groceries, so food brought in from outside could not be trusted. It was also unclear if the water in the taps would be safe and how tight the window and door locks would be. We put extra protection on the windows and insulated the doors and all other openings, including ventilator openings. As in Covid-19, we had to protect against an invisible enemy with no clear knowledge of the surface risks already in the flat, and no ability to be sure when the danger passes.

After four days, the Russian Communist Party owned up to the accident, but classified it as “awaria” – roughly translated, “fairly minor incident”. The official Polish communist propaganda version published in Trybuna Ludu on 30 April 1986 was that there was no danger to humans and “the level of radioactivity was the same as in tower blocks” from radon. At the time, radon in building materials was thought “safe”; the irony of the comparison was not lost on later generations of Poles when, much later, the danger of radon was eventually revealed and its role in causing higher rates of leukemia among tower block inhabitants was understood. Initially, the government even advised that “vegetables can be eaten after careful scrubbing with hot water”. The familiar pattern of giving the hapless population some small, routine over which they can have a sense of control over is a well know behavioural scientists’ trick.

The negative impact of the nuclear fallout in Warsaw, the city most affected by the path of the radioactive cloud, was exacerbated by the Polish communist government’s obsession about the 1 May Labour Day celebrations. I still remember our shock when we heard that the Sunday paper (which we had not seen in our self-initiated lockdown) in bold fonts encouraged people to join the marches, next to a tiny announcement of the Russian “awaria”. In those big parades, anyone who could hold a flag, from pupils to sports teams, teachers, and workers, had to march pointlessly for hours from various parts of town to meet in a triumphant pro-communist tribute on the main square. Like most of the rest of Warsaw by then, we continued with our lockdown. The government was still in denial, frightened of the anti-Russian sentiment announcing the truth would cause.

Here again, our basement corridor connections were crucial, allowing us to visit our friends and neighbours within our block. As always in a crisis, those corridors of salvation were turned into party environment, made easier by the many basements already being used for brewing beer or vodka because of communist rationing and food shortages. Again, compote and pickled mushrooms made a comeback as menu items for basement parties.

As the scale of the catastrophe became better understood, Polish government broke ranks from the Russian official line and eventually advised people to stay at home, shelter in place and stop eating food from affected areas – roughly 40% of Poland. They also organised a prophylactic supply of an iodine drug called Lugol, albeit only for young children and teenagers. On 2 May, Rzeczpospolita, the main government mouthpiece, printed the top general’s 1 May speech, but contained only a small note about young people needed to take. It was not well explained that the excess of iodine 131 that was spat out during the disaster was highly cancerogenic and only Lugol could mitigate the effects. Officially, the prophylactic liquid was just “advised” and only for young people. Later, leukemia, thyroid cancer and other health issues caused by the disaster appeared in the older population who did not get Lugol (mainly because there was a shortage, like protective masks now). I was a few years too old to qualify for Lugol, and wound up with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis as a result of radioactive exposure, despite our 14 days’ lockdown. The difficulties of living with it is a lifelong reminder of what why we must not blindly trust government health advice during large-scale medical emergencies.

After two weeks, we concluded the cloud and its impact must have passed. Nobody really knew, but we had to go to work as no sick pay was offered and no excuses were accepted while the Communist Party stuck to its “harmless radon” line. In the absence of honest government information, many myths about cures for fallout circulated, some looking more promising than others.

Some of our more entrepreneurial friends who also did not qualify for Lugol organised transport of “Jelinek” gin from Czechoslovakia, which contained similar components to Lugol and remained a popular drink of choice as a prophylactic for many years afterwards. It tasted like medicine, very bitter, so that helped the psychological sense that it might be helpful to health. I drank a lot of it. I still got Hashimoto’s disease – but not thyroid cancer (yet). Was it a myth? We will never know.

Controlling fake news around those medical emergencies in the lockdown is a real challenge now as it was then. Even in communist Poland with no mobiles and very limited landline coverage, news about various “cures” spread fast, with desperate people trying ridiculous solutions to protect themselves and families. Many women decided to have abortions, even late ones, as fear of the impact on the unborn was high and doctors recommended it on the quiet.

For years afterwards, many people stopped eating bread, as there was a rumour that the spring cereals just sprouting in the fields would have been affected by radioactivity. It may have been true but, it led many small bakeries into bankruptcy – a double blow, as bakeries were one of the few private sectors that thrived under communist regime, mainly because the big state bakeries’ bread was awful. Meat and meat-originated dishes were also off the menu, as the radioactive cloud moved over agricultural areas, affecting the health of millions of cows, sheep, and chickens.

It was very hard to figure out what was safely edible, and for months many families resorted to canned food, pickles, fruit compote (something that well-functioning Polish households would prepare in the summer in glass jars to last the long Polish winters) and other items that were prepared and packaged before the fallout began. Feeding my six-year-old niece and keeping her safe was a daily challenge for the year following the fallout, as the government stubbornly refused to clarify the situation, probably through fear of panic and lack of alternatives. We boiled everything: no fresh fruit was consumed that summer and only heavily treated vegetables were allowed on the plate.

Lack of transparency in medical lockdowns is one of the biggest challenges for governments face; it leads to epidemics of misinformation, panic buying, and chaos. The must find a balance that stops people from spreading snake-oil miracle cures but doesn’t block genuine news, such as the shortage of appropriate masks for junior doctors. Too much censorship, and the opposite effect is achieved, when people resort to alternative channels and just don’t believe anything they hear.

What I’ve learned from my three lock-downs is simple: always have a full larder and freezer, bread flour and yeast, and at least one month’s supplies, as disasters come unannounced. Lockdowns, be they a medical emergency, biowarfare, or political, rarely give you a heads-up. Having fresh bread makes a difference to everyone’s mental health and reduces the need to leave the house, which in disasters may be dangerous or impossible.

Arm yourself in your own Geiger counter for independent measurements and make friends with virologists. Covid-19 will not be the last pandemic in your lifetime. Buy gas masks; they are handy in biological disasters and don’t take much space. Run a drill once a year for family members to make sure they know how to put it on. Do make sure there is an underground connection to your neighbours’ basement – or create one by providing air-tight connected covered passages aboveground. Finally, don’t forget home-brew beer kit or vodka making equipment. It not only helps to pass time, but alcohol becomes a currency when the value of money disappears. Which by my reckoning, watching the magic money trees exploding, we will face in UK very soon indeed.