The Valens Program

Written by Jesse Rowell for ‘Tales from Cybersalon’, September 2021.

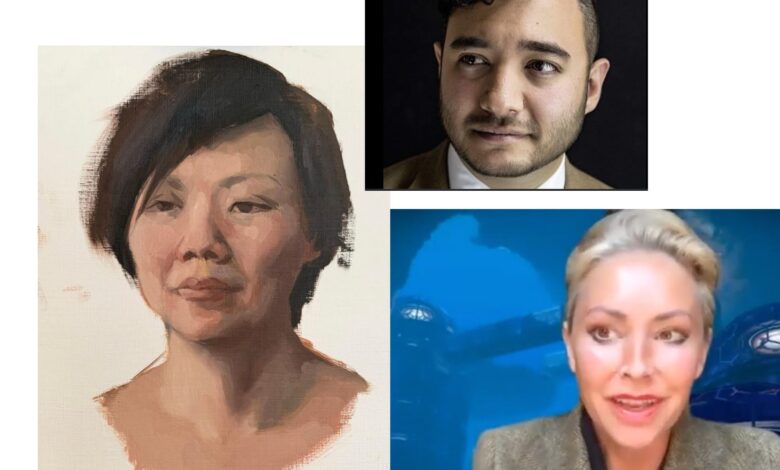

Shale oil extraction below the Sangre de Cristo Mountains unearthed imaginary people in July 2069. People preserved on paper, mostly villains, that never existed. Details of their lives spanned decades in the documents hidden under Valens, an isolated community that had been led by Murphy Vega in the 1960’s. For what purpose did he bury his creations, the painted portraits and doctored photographs of a nonexistent population?

The Valens Program rose to prominence claiming to have stabilized several small nation-states facing crises a century later. Filing for IPO in 2075, founder Tripp Staveley has never referred to the historic community that shared his trademark, but he has relied on a similar strategy of manufacturing deviants for a targeted audience. Valens’ inauspicious beginnings and current success is a cautionary tale as to what could become of our shared reality.

Valens’ mission statement, Strengthen to Stabilize, originated from Staveley’s time spent in isolation. An unknown illness banished him from his boarding school to his father’s New Hampshire estate where he watched cottontail eat clover outside his bedroom window as he endured years of physical therapy. The idea of incremental improvement through exacting process came to him as he relearned how to walk and mastered archery. After recovering from his illness he used a recurve bow to kill most of the rabbits around his father’s estate.

Like all technology startups in the 21st century, family money buoyed Tripp’s ambitions as he sustained large revenue loses. It wasn’t until the antitrust breakup of social media companies that Valens turned profitable taking over government contracts for countries on the verge of collapse. Staveley remained reticent on his initial success, but much of the credit can be attributed to his AI-constructed deviants.

Referred to internally as the Lotus Server, a reference to the lotus-eaters in Greek mythology, the company created deepfake deviants with family histories and years of social media postings, photos and videos for communities to examine and vilify. The ghosts that the Lotus Server wove into the fabric of society became so effective as to become hyperreal. People claimed to have known the deepfakes at some point in their lives, gone to school or worked with them, and above all, hated them. Murphy Vega had described it a century earlier as hijacking community malice and redirecting it toward ghosts. To assuage discontent in the Valens community in 1962 he deployed his own primitive version of a deepfake after several children contracted plague from prairie dogs. He directed the community’s ire toward a traveling salesman who didn’t exist, but whom the community blamed for the outbreak and burned in effigy after listening to deceptively edited audio recordings. Stability followed the banishment of the imaginary salesman and he became part of the community’s lore.

People are primed to accept deepfakes, Staveley noted in his research, when the campaign aligns to their worldview, political ideologies, or base desires. The Lotus Server aggregates data from consumer behavior and internet search history to craft a shared valent event that plays on the fallibility of an individual’s memories and a community’s collective memory. Staveley described it as somebody yelling into a crowd, “Hey, you should all hate this thing over there, okay? Good, now we’ll take care of it for you.” Spark outrage, offer resolution, and reconcile cognitive dissonance. “Guide an entire community back to health.”

Take the curious example of the Birch Bower Incident, named after the clandestine location where lobbyists for the mortuary industry met, a forest of white bark pockmarked with black eyes staring out in all directions. In numerous leaked videos the lobbyists discussed dismantling public health mandates during the 2081 pox pandemic to profit their clients. Roundly condemned by politicians in both parties, legislation quickly passed to increase health measures saving countless lives, and the lobbyists were publicly shamed. Debate continues to this day if the lobbyists were creations of the Lotus Server or real people as some have claimed to have known them or be acquainted with distant members of their family.

Staveley has pushed back at the criticism leveled at his company for creating alternate realities saying, “Who wants a return to illness?” Accomplishing peace in the present by distorting the past justifies the Valens Program, he has asserted, and that communities escaping poverty and violence would agree with him. Staveley has maintained that creating fictitious deviants guarantees that no real people get hurt, and that the Lotus Server is such a small part of the Valens portfolio of business as to not warrant further scrutiny.

All forms of disinformation require scrutiny, academics and researchers counter, even if deployed with altruistic intent. The AI-generated deviants cannot be created devoid of identifiable characteristics like ethnicity, religion, and culture, which has resulted in hate crimes directed at other communities based on the perceived origins of the deviant. When the success of a community is measured by its shared experiences and the open exchange of ideas then gaslighting and lies become uncontrollable vectors that impede community progress.

Murphy Vega tried to bury his creations under shale and sandstone. The community he once led now lies in ruins, a ghost town of broken boards and wall insulation made of newspaper flaking off like yellow leaves in an autumn wind. The imaginary people he sought to hide from the world live on as objects of derision in a failed social experiment. Tripp Staveley, who has ushered us into the new

Valens era, would be wise to learn from the lessons of history, that is, if he can find a history that has not yet been altered.