Lost in translation – what has gone wrong in digital health!

When supposedly personalised, medical app for your health goes wrong, you may get cut off from your insurance, your house, your place in society and ultimately, your life. The irony is that you don’t get any personalised service from these apps when things go wrong, just a generic ‘computer says no’ from the app provider.

This truly nightmarish scenario was explored by Jule Owen’s short sci-fi noir story about Smart Health data apps, written for the new series Tales From Cybersalon, futures of digital health.

In her story, the main hero is slowly but mercilessly and efficiently cut off, step by step, from his identity, his work, his own home and his whole existence by an automated Health Insurance app. It is like updated Kafka story for 21st century, and as in Kafka, it does not end well.

The story is picking up from the mega consolidation in European Digital Health, as Health Hero , UK telemedicine leading app was allowed to merge with Qura, market leader in France, creating a group of 22mln customers. You are not a patient anymore, not a familiar face to your GP, but just an ID, a reference in a number of different computer systems that are often not compatible.

Responding to increasing concerns about the handling of our medical, often very intimate and personal data in UK and US by faceless digital health giants, Cybersalon has organised an open call for short sci-fi stories. The brief was to re-imagine the impact of the hyper fast growth in med data gathering and medical/insurance apps- created around Covid, NHS and mobile phones providing ‘captive audiences’.

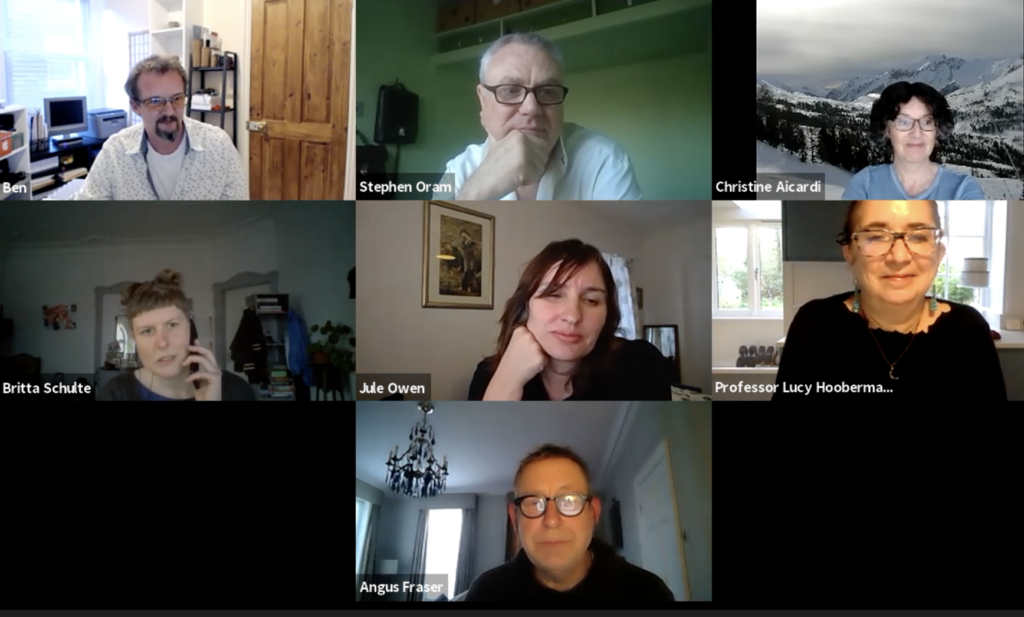

Eva Pascoe hosted the even on behalf of Cybersalon with writers like Jule Owen, Britta F Schulte, Stephen Oram and Ben Greenaway who have all been selected to present their Smart Health sci-fi stories to Cybersalon audience.

The idea came from an insightful book titled “Imaginary Apps” by Paul Miller (aka DJ Spooky) published a few years ago. In his book, Paul has asked a few artists and writers to imagine an app that has not been written yet. The taks was to consider a plausible app that can be written within the current technology, with the author thinking thru app’s implications. Our favourite was an app “How To find Good Luck” or GPS for those in need.

We took the idea to our panel of sci-fi writers, inviting them to re-imagine apps and medical data gathering scenarios that will be arising from currently supercharged process of digitising health, or “Smart Health” as it is known today.

The stories are here on Medium as well as here (on video- where writers read their 5min works for the panel of invited public health care and tech experts like Dr Christina Aicardi from Brain Project, Prof Lucy Hooberman (Warwick Uni) and Gus Fraser (AI For Face Masks Compliance start-up).

The writers read their short stories, ranging from Robo-Bot for Health Insurance app going tragically wrong (by Jule Owen) , a food-whores brothel where people pay vagrants to eat the unhealthy food for them (by Stephen Oram), examining the case of elderly medical surveillance app gone rouge (Britta F Schulte), to being lured into swapping your health data for a rare chance to travel to space (Ben Greenaway).

None of the scenarios produced by our writers looked like the future we actually want to inhabit – very much as in the comment of John Von Neumann about computer inventions:

What we are creating now is a monster whose influence is going to change history, provided there is any history left.

What is timeless, is the propensity for the system to quickly become super rigid and unforgiving. As Eva Pascoe noted, a lot of AI and Health Bots mishaps are very similar in consequences to regular Eastern European communist bureaucracy that she had grown up with.

The system was analogue then, just paper-based, but equally faceless and merciless. There was no recourse if it went wrong for an individual and ultimately led to dis-functional society that people rejected as soon as they got a chance.

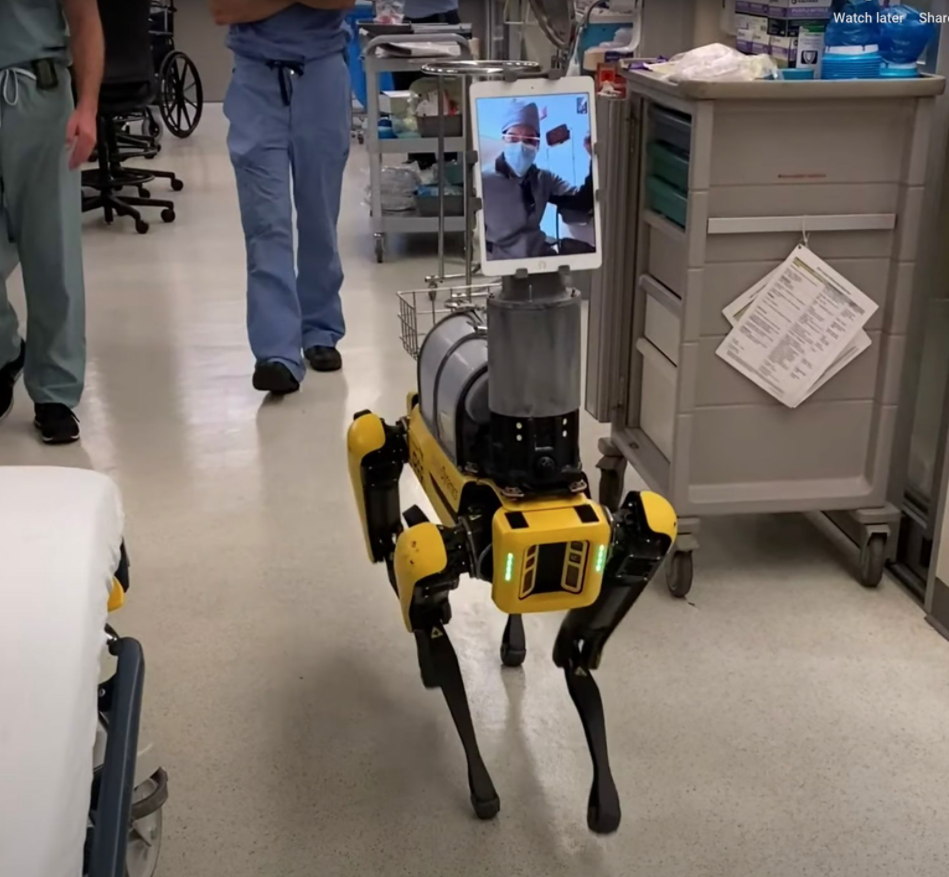

Today, many billions of dollars later, the irony is that we ended up with similar, faceless AI Health Bots that fail to truly serve people and are increasingly causing unease amongst patients, users and public health experts alike.

Christina Aicardi (AI Ethics Lecturer in King’s College, Foresight Group and Brain Project) notes that the state of medical surveillance has got to the point when tech is actually a threat to our health and hindrance to well-being rather than a solution.

It is time to re-think.

When assumptions are wrong, the app is doomed to fail

Christina notes that all the medical alerting apps are underpinned by a kind of standardised concept of an ‘average’ person, in this case, with Britta’s story, an average elderly person.

The apps assume that elderly people are all the same.

In the real world, older people are not a homogenous tribe, there are significant, large differences between them, as in the story, some may have active sex life, some may party, others may like exploring and getting out of their geographical boundaries.

It is that assumption of ‘averageness’ which causes lack of privacy to the surveilled individual, and anxiety to the family who is looking after them.

Following the change in our relationship with our bank manager, which moved from personal to us just being a number for a Machine Learning system, now the same is happening in health, notes Gus Fraser, AI entrepreneur and advocate of ethical use of date.

Today, instead of having face to face contact with a GP, we get a chat bot directing us to some online services, where never ending routing system leads us to nowhere.

Our medical Data, once disaggregated, turns each of us from an individual into a soul-less, abstract concept who is all but a set of numbers that algorithm can process. Once stripped of our individuality, we can’t fight back, as we are only zeros and ones, notes Professor Lucy Hooberman (Warwick University)

How to tackle rouge big data and idiotic Robo-Insurance apps?

Both writers’ group and our panel have agreed that the issue is low understanding of the risks of leaking medical data and lack of informed public debate on med data topic.

It is not just that the elderly surveillance apps cause anxiety to carers if the person being cared for goes off the beaten track.

It is the assumption that Big Data is Good Data, that gathering all the medical data that private apps can eat will somehow turn into gold.

So far the evidence of automating health care via apps has not been a success. To the contrary, it leads to automated, Kafkesque, machine-learning nightmare for the poor, while retaining personal contact and private GPs with face to face contacts for those who can afford premium private health.

In addition, as Dr Christina notes, health apps often start well as well-meaning health tools. But a couple of hostile takeovers later – as it was her experience with one of her previous jobs in medical engineering company – the new owners are only ever going to look at the data as the new oil, to be exploited and abused as long as ‘compliance’ can be paid lip service to.

She also notes that new, hyper fast development in digital map creating and enrichening the data with personal addresses or details has created new, severe risks, sharing information about all sorts of behaviours linked to localisation that were never meant to be public.

UK Track and Trace app mishaps

Case in point is the latest, attempted update to UK Track-and-Trace app, that UK government was asking Google to upgrade on the app, for UK users to upload their list of visited venues.

If the person tested positive, the list of venues was meant to be shared via the app and messaged to others, who might have visited same venue.

Google and Apple refused to cooperate, as under their terms they had stipulated right from the beginning, it was a nono to collect any location data via the software.

Both Google and Apple felt compelled to reject the request to update the app with extra location data that UK government has requested, and explained that from the onset, they were offering the app service but not the venue tracking element – to protect individual privacy.

Scotland has avoided the problem by creating a separate Check In Scotland app to share venue histories. It is uncomfortable to think that UK government had to be correct in their understanding of medical privacy by two tech giants.

We live in a new world of Big Tech becoming ‘protectors of digital privacy’ – not a state of affairs anyone would have predicted back in 1997 when we were arguing with Google against then new Third Party cookies and their blatant abuse of personal privacy.

Things have changed but now we are in hock to big tech as well as big government.

Escaping the privacy nightmare

How do we become gatekeepers of our own data – asks Gus Fraser.

Crypto community may be showing the way, as with Bitcoins, you and only you are responsible for keeping your passwords save and secret. If you lose the password, your bitcoin treasure goes up in a puff and no bank manager will rescue you.

However, the panel noted that this is an unlikely scenario for working out safe handling of medical data, as most users are not able to maintain such a degree of self -organisations and self-reliance.

Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of World Wide Web, has a project for personal Data Pods, where we as users own our data and allow access case by case, permission by permission.

This is an idea with many fans, but technically needs to be user friendly and slick to allow seamless trade for users and companies.

We are not close to have infrastructure on those lines up and running in the near future, although it is not to say it will not be possible to construct, with cooperation of Apple or Google (none forthcoming so far).

Off the grid

There are some more radical voices, noted Gus Fraser, which advocate getting ‘off the grid’ and not entering your data where you don’t want them to be leaked.

But how realistic scenario is that – considering everything from HRMC to gov.co.uk force us to enter data, yet both (and hundreds of other, essential service providers) have been hacked many times.

As Gus notes, a quick trip to can show the depth of your exposure to stolen passwords, credit card details or addresses, revealing the extent of your data availability to hackers.

Eva Pascoe notes that it is about time to strike back and use Open Source to start actively creating alternatives, tests and pilots to ‘Re-Occupy Technology’ – take active step towards building alternatives and testing users’ acceptance of different approaches to privacy.

Separation of data from the individual is where things are go wrong and where law must be used to protect this link against rouge AI.

Data Owners Unite

Eva Pascoe suggest forming Data Owners Union, a collective organisation where, like in a political party or cooperative, we agree to share medical data but only amongst the collective and with constant safeguards and transparency of use reported to all users. Elected ‘trusted representatives’ would oversee closely the handling, storage and availability to research of the data.

Good example can be used from Retail data, stored in Said Business School Consumer Data Research Centre and guarded by a set of rules agreed amongst data donors – mostly large retail companies who need to care about compliance.

Professor Hooberman noted a project based in Boston, where patients actively agreed to share their health data for a pilot on data use. They were happy to share on consideration this was for one off.

However, this works for one off use, but safeguarding such data for the future is a lot harder task, one that nobody in NHS has a good answer for.

Eva Pascoe mentioned the need for the community to protect themselves is usually the main driver to the new laws. A new EU law about granting rights to homeless has been recently accepted, showing that if a community feels it needs protection, that legal framework can and should be granted.

Data, like any information has a social life, and one that needs to be examined if we as a collective are to benefit, notes Dr Christina Aicardi . She urges the researchers to review this ‘life of data’ and use maybe more ethnographic, holistic approach to review how this asset should be protected against bad outcomes. A good book on the topic is Social Life of Information, reminding techno-fans about human socialbility being the central aspect of interpreting the data.

One of the answers may be individual access to all medical data kept by all companies and also ‘right to be forgotten’ in medical data stores.

Is your Medical Data similar to your country pub?

Community pubs are considered protected public asset in UK.

Professor Lucy Hooberman gives example of her local Norfolk pub and the battle for taking it under Public Asset protection.

She suggests that we should tag collective medical data as similar, protected public assets and ensure the government has to treat it with care.

Embedding this status in law would prevent your medical data subject to asset stripping, repetitive, partial but continuous selling-off NHS data to private start ups (or large companies like Palantier or Google).

This is a promising direction of work towards improving medical data privacy, although Gus Fraser sounded a note of caution that ‘society can only protect individual so far, ultimately we are responsible for protecting our own assets and medical data assets are not different”

The panellists and writers concluded that use of sci-fi short stories as a way to re-imagine what are the true consequences of some of the new tech is an useful direction, and one that public outreach bodies should consider. Imaginary Apps stories open the conversation about protecting our medical data in a way that this often dense topic becomes closer to everyday experience.

The challenge of low awareness and the need for re-educating users to protect their medical data and to support the collective use of data has never been greater and we were grateful to our writers for making such a great contribution!