Lost Dreams of the American Future

Interstellar travel, nuclear fusion for everyone and thinking machines: The 1964 New York World’s Fair promised a new revolution of everyday life, an age of understanding. Far from visions of peace and progress, beneath the façade, a celebration of world conquering military technology. Fifty years on, argues Richard Barbrook, and we have to contend with the two opposing visions of that dubious military project, the Net.

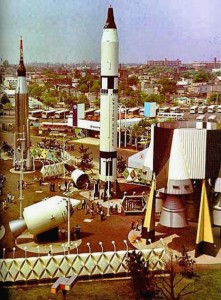

Welcome to what was once the greatest show on earth! This year marks the 50th anniversary of the first season of the 1964/5 New York World’s Fair. I know because I was there as a 7-year-old boy and I can still recall my excitement at seeing the giant rockets in its Space Park. Having just arrived from England, the Barbrook family’s day out at the World’s Fair was one of my earliest encounters with the weird and wonderful culture of what would be my temporary home for the next 12 months. My father Alec was on his way to begin a research sabbatical at MIT’s Political Science department which – as I later discovered to my amusement – was surreptitiously funded by the CIA. Since these spooks’ goal was to persuade Europeans to embrace the American cause, spending some of their grant money on our family excursion to the 1964/5 New York World’s Fair was most appropriate. Symbolising its organisers’ ambitions, the centre piece of this exposition was a 43 metre stainless steel sculpture of planet earth: the Unisphere. Laid out around this impressive icon was a complex of pavilions sponsored by US government institutions, private corporations, friendly countries and faith communities. Wandering around these exhibits, the Barbrook family and other visitors to the World’s Fair could – among its many spectacular attractions – watch a musical about the marvels of chemistry, take a Disney ride explaining the evolution of life on earth, lunch in an imitation Belgian village, go on a Pop Art ferris wheel, gaze at a domed roof shaped like the moon and stand underneath 9 life-size replicas of dinosaurs. The best of everything from all corners of the globe was on display for us to savour.

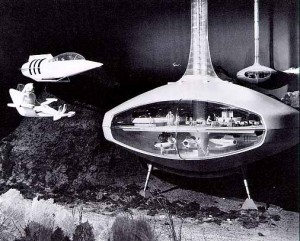

Above all, the crowds at this exposition were expected to admire the unsurpassed technological prowess of the American empire. In both its state and corporate pavilions, what had already been achieved was proudly displayed as the promise of the shape of things to come. The Mercury and Gemini rockets which so impressed me as a small boy were precursors of the space liners which would one day be taking holiday-makers to the moon. General Electric showcased a demonstration of atomic fusion which would soon be providing almost free energy for every business and household. Launching its new System/360 mainframe, IBM boasted that this computer was the prototype of machines that would be able to reason like human beings: artificial intelligence. The patriotic message of these fabulous exhibits was unambiguous. The USA was the hi-tech future of humanity in the present. Inspired by this utopian prophecy, the peoples of the world were now adopting the American way of life with enthusiasm. Within a couple of decades at most, we would all be able to travel into space, use electricity without worrying about its cost and buy robot slaves to serve our every need. Science fiction was on the verge of becoming everyday reality.

Ever since the stunning success of Victorian Britain’s 1851 Great Exhibition, ambitious elites have been hosting international expositions to promote their own country’s scientific advances, cultural accomplishments, geopolitical influence and economic achievements. For instance, like Beijing Olympics two years earlier, the recent Expo 2010 in Shanghai was conceived as a public celebration of China’s reemergence as a great power. East Asia was once again at the centre of the global system. Five decades earlier, when the 1964/5 New York World’s Fair opened, its organisers were similarly confident about the USA’s exceptional status. In the year that the Barbrook family visited this show, there could be no doubt that America was Number 1 in every key indicator of national importance: political freedom, living standards, financial hegemony, industrial output, artistic creativity, military might and, as its corporate and state pavilions kept emphasising, technological progress. Crucially, on all of these measures, its Russian rival was a poor second in the Cold War confrontation between East and West. Not surprisingly, like so many Europeans of his generation, my father took pride in his enthusiasm for the American empire. Being awarded a grant to study at MIT merely confirmed his long-held loyalty to the most advanced civilisation in human history. In 1964, as our family visit to the New York World’s Fair confirmed, the West was the best.

Nowhere better conveyed this geopolitical message than the exposition’s Mercury and Gemini rockets. Like most small boys at that time, I was obsessed with the heroic adventures of the astronauts and cosmonauts who were competing against each other in the space race between the USA and the USSR. I too fantasised about flying to the stars with John Glenn – and embracing Valentina Tereshkova in zero gravity! As my mother fondly recalls, my top priority for our family visit to the World’s Fair was going to the Space Park. Although the Russians had taken an early lead, its Mercury and Gemini rockets proved that the Americans were now surging ahead in this superpower contest for technological supremacy. Before the decade was over, the USA would win the space race when its astronauts made the first landing on the moon. Yet, despite this impressive triumph, the predictions of interplanetary tourism made at the 1964/5 World’s Fair have yet to be fulfilled. If the 7-year-old Richard had been able to look forward to now, the fact that it’s impossible buy a ticket to the moon in 2014 would have been most puzzling. Unfortunately, like almost everyone else at the exposition, I’d been misled about the true purpose of the huge rockets in the Space Park. Far from being Version 1.0 of starships, they’d been developed for a much more diabolical purpose: the mass murder of millions of civilians. Guided by computers, these missiles were capable of delivering a nuclear bomb which could wipe out an entire Russian city and its unfortunate inhabitants. Not surprisingly, the management of the World’s Fair had no wish to terrify its visitors with the imminent threat of atomic armageddon, especially as the Cold War enemy was also equipped with these horrific weapons. Instead, concealing their military origins, intercontinental missiles, nuclear reactors and mainframe computers were rebranded as the precursors of space tourism, free energy and thinking machines. Except for the perceptive few, the happy crowds enjoying the Pop Art architecture, Broadway shows and Disney rides of the New York World’s Fair were unaware that all around them on public display were the mechanisms of genocide. In the West as in the East, optimistic propaganda had replaced critical understanding.

Five decades later, the Cold War prophecies of extraterrestrial tourism and fusion power are still being plugged by the promoters of Virgin Galactic’s space planes and the EU’s experimental HiPER reactor. For them, the techno-utopian future is what it used to be. More surprisingly, there are even some scientists who also believe in the imminent arrival of artificial intelligence. Yet, the history of computing since the 1964/5 New York World’s Fair has taken a very different path from that predicted by its IBM pavilion. Instead of enabling expensive room-sized machines to mimic human brains, continual improvements in hardware and software during this intervening period have shrunk the expensive System/360 mainframe into today’s affordable laptops, mobiles and tablets. Above all, over the past fifty years, computing has converged with telecommunications and the media to create the iconic technology of our own times: the Net. At the New York World’s Fair, IBM’s computer which could read hand-writing, Bell’s prototype videophones and the model of the Telstar satellite circling the Unisphere were premonitions of this ubiquitous necessity of modern living. Capturing the emancipatory possibilities of these scientific advances, its organisers declared that their exposition was dedicated to construction of global harmony: ‘Peace through Understanding’.

Unfortunately, just like the Mercury and Gemini rockets in the Space Park, network computing is also a Cold War technology which was invented for malign purposes. In America as in Russia, it was military money that funded the pioneering scientific research into digital hardware and software. During the two decades before the 1964/5 New York World’s Fair, IBM’s success in securing defence contracts had transformed the corporation into the dominant player within this cutting-edge sector of the economy. Every machine from its first commercially available mainframe series – the aptly-named 701 Defense Calculator – was sold to either the US military or weapons manufacturers. IBM developed both the graphic user interface and remote computer terminals for the SAGE command-and-control system of the American bomber fleet. Crucially, it was while working at the US airforce’s RAND think-tank that Paul Baran published his seminal 1960 paper on packet-switching data networks. One carefully-aimed Russian atomic bomb could disable America’s imperial power by destroying the central node of its military’s top-down hierarchy. In his RAND report, Baran argued that IBM’s SAGE provided the prototype of a digital solution to this mortal danger. By enabling the flow of orders to route around any damaged links within computerised communications, his packet-switching software would ensure that the USA’s armed forces could keep on fighting against the Russian opposition even if its General Staff headquarters was knocked out of action. In this first iteration, the Net was a command-and-control system for waging nuclear warfare.

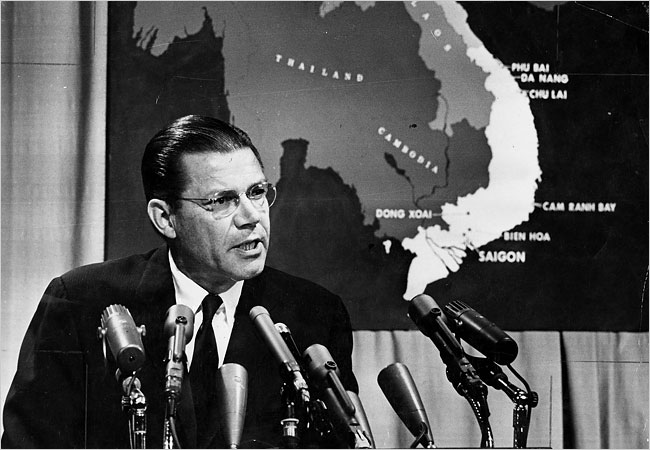

While the crowds were still flocking to admire the technological marvels of the New York World’s Fair, America’s political and military leaders were seduced by their own futurist propaganda into making one of the most disastrous decisions in this nation’s history: the invasion of Vietnam. Back in the mid-1950s, when the French empire was evicted from its South-East Asia colony by a Maoist peasant insurgency, the USA had intervened to secure the southern half of the country for its local supporters. But, by the time that the World’s Fair opened a decade later, this corrupt and brutal pro-American client state was in deep trouble. With organisational and logistical help from the independent north, Maoist guerrillas had taken over most of the countryside in the south and were on verge of seizing control of its major cities. Refusing to concede defeat in this Cold War confrontation, the rulers of the American empire in 1965 decided to send out a massive expeditionary force to subdue this rebellious frontier province. In contrast with the defeated French colonialists, the US military now possessed advanced digital technologies which could secure victory on the South-East Asian battlefield. Using IBM System/360 mainframes, its staff officers planned the bombing campaigns and ‘search-and-destroy’ missions that were launched against the Vietnamese partisans. By measuring the losses of American troops and their local collaborators against those of the resistance fighters and their civilian supporters with accountancy software, US generals had statistical proof that the West was winning its war against the East: the ‘body count’. Named in honour of the politician who managed this colonial campaign, the McNamara Line was built as an impenetrable electronic barrier between the two halves of Vietnam. When its vast array of networked sensors detected reinforcements from the liberated north crossing into the occupied south, they alerted the computers monitoring this Asian equivalent of the Berlin Wall which then directed American aircraft and helicopter-born troops to intercept and eliminate these Maoist subversives. In this second iteration, the Net was a top-down surveillance technology for imposing the empire’s domination over the restless natives of its border regions.

As they toured the marvellous exhibits of the New York World’s Fair, the overwhelming majority of visitors didn’t realise that its corporate sponsors were already making huge profits by providing the machinery of death and destruction for the US military’s assault on Vietnam. Inside the IBM, Bell and General Electric pavilions, the hi-tech promise of global peace was hiding the barbaric reality of imperialist butchery. Fortunately for humanity, over the next decade, the bravery and ingenuity of the Vietnamese partisans slowly but surely overcame the massive superiority in material and manpower of the American army of occupation. In the end, like the Berlin Wall, the McNamara Line couldn’t prevent the unification of a country whose people were determined to be united. Yet, as the recent revelations by Wikileaks and Edward Snowden have reminded everyone, the 1975 victory of the Vietnamese national liberation struggle only intensified the US military’s enthusiasm for network computerised warfare. Next time, its upgraded hardware and software must be able to beat the bad guys. By the time that Bush administration decided to invade Afghanistan and Iraq in 2001, American generals were convinced that their soldiers were now invincible on the electronic battlefield. Hi-tech weaponry was their substitute for intelligent geopolitics. But, having failed to learn the lessons of Vietnam, the US elite has once again suffered humiliation in these 21st century imperialist adventures. As the foot soldiers are slowly withdrawn from the badlands of the Middle East and Central Asia, the National Security Agency (NSA) has now emerged from the shadows to take a frontline role in the defence of the American empire. By intercepting phone calls, emails and social media postings, its spies are already able to provide the terrain coordinates for many of the US military’s deadly strikes against suspected Islamist terrorists. When the NSA has the whole of humanity under constant observation and American drones are continually patrolling the world’s skies, all overt resistance to imperial domination will become suicidal. In this 21st century reboot of the McNamara Line, the global hegemon punishes evil thoughts with sudden death from above.

Still traumatised by Al Qaeda’s murderous 2001 attacks on New York and Washington DC, the overwhelming majority of the American population strongly supports their government’s repressive measures against terrorists in distant countries who threaten the safety of mainland USA. Even Snowden’s exposure of the NSA’s phone tapping of leading European politicians has aroused little protest. When American lives are in danger, the human rights of foreigners are irrelevant. However, as the inhabitants of earlier empires also discovered to their cost, despotism abroad almost inevitably inspires authoritarianism at home. According to the 1791 Bill of Rights, every US citizen is protected from the worst abuses of state tyranny, including the interception of their personal communications except in exceptional circumstances which require judicial authorisation. Already much eroded during the Cold War, this constitutional guarantee was negated by the mass panic unleashed by Al Qaeda’s 2001 terrorist atrocities. Having obtained the approval of both the legislature and the courts, the US government ordered the NSA to monitor the personal communications of anyone who might pose a threat to the American empire. Flush with taxpayers’ money, its spooks have spent the last decade and a half constructing the technical infrastructure for the ubiquitous surveillance of the entire global population. More than anything else, the realisation of this totalitarian ambition has depended upon the dominance of corporate America over the Net. Whether for targeted advertising, market research or customer relations, these dotcom companies have become adept at gathering and analysing data about how people are using their products and services. For the spooks, gaining access to this confidential information which can reveal an individual’s political opinions, moral beliefs and cultural tastes is a top priority. Like the corporate sponsors of the New York World’s Fair that profited from the American invasion of Vietnam, some dotcom companies such as Microsoft have voluntarily included back doors in software to facilitate NSA spying upon the purchasers of their products. Others with more scruples like Google have instead had the traffic to their servers surreptitiously copied by the American secret police. Crucially, this mission to accumulate intimate digital data is no longer confined to the brown-skinned inhabitants of the troubled frontiers of the imperial realm. With the 1791 Bill of Rights eviscerated, the NSA can now also intercept the personal communications of all-white American citizens with impunity. Since anyone could be an enemy of the empire, everybody must be a potential target of surveillance. Invented as a military technology, the Net promises to provide the US elite with a decisive technological advantage in the perpetual war against its real and imagined opponents at home and abroad: total information awareness. The organised few will always prevail over the disorganised multitude.

On both sides of the Atlantic, much of the anger directed at the NSA’s illegal spying is fuelled by the shocked realisation that the libertarian prophecies of the Net boosters have been disappointed. Back in the mid-1990s, the writers of Wired promised that the convergence of computing, telecommunications and the media would soon sweep away the state and corporate hierarchies which curtailed personal creativity, individual freedom and entrepreneurial initiative. In their Californian vision of the digital future, anyone with a good idea and a bit of luck has the opportunity to become a dotcom millionaire. Echoing this neoliberal prediction, many leftists over the past two decades have also embraced the emancipatory possibilities of the information society. Bypassing the ideological conformity of the mainstream media, radicals can now utilise social media to proselytise and organise against the exploiters of humanity and the plunderers of the planet. As proved by the 2010-1 Arab Spring and the 2011-2 Occupy movements, the Net is creating the technological infrastructure for mass participation in democratic decision-making. Unfortunately, like the crowds at the 1964/5 New York World’s Fair, the believers in these two variants of digital libertarianism have been mesmerised by the wonderful civilian spin-offs of a dubious military project. As Snowden’s leaks remind us, the Net wasn’t invented to open up new markets or foster political diversity. Like the rockets which so impressed the 7-year-old Richard in the Space Park, it is first and foremost a Cold War weapons system. Far from perverting its true purpose, the NSA’s grandiose scheme of ubiquitous global surveillance is the fulfilment of the Net’s founding mission: defending American imperial hegemony over a chaotic world.

According to some clever hackers and resourceful entrepreneurs, the menace of digital totalitarianism can be countered by developing strong forms of encryption for the masses. However, as the recent arrests of the sellers of recreational drugs on Silk Road 2 demonstrated, this technological fix is unlikely to provide a long-term solution for protecting personal privacy. This growing realisation of the inherent weaknesses in Tor and other encryption programs has encouraged the rediscovery of more traditional countermeasures to state tyranny. Tim Berners-Lee – the revered creator of the first web browser – is now calling for the formulation of a new Bill of Rights for the Net. Even if the NSA could be made to respect the US constitution, Americans would carry on spontaneously flouting its legal protections of their own privacy.

Thanks to the Net, sharing personal information with strangers is now a prerequisite of everyday existence. From finding directions on a map to buying next week’s groceries, people are continually revealing the most intimate details of their personal lives to all and sundry. As Berners-Lee has understood, the liberal concept of the self-sufficient individual which inspired the 1791 US Bill of Rights is now obsolete. What is required instead is a new political settlement which nurtures today’s collective forms of digital citizenship. Personal freedom on the Net is threatened by the intrusive attentions of both state and corporate hierarchies. If the emancipatory promise of the information society is to be fulfilled, people must be confident that their informed consent is required to access and utilise their private data. The fear of secret police surveillance and corporate monitoring is already inhibiting the expression of dissident views on social media. By ensuring that freedom and democracy aren’t sacrificed for security and profits, the Net Bill of Rights can provide the mutually agreed rules for regulating the 21st century’s network society in the common interest. In cyberspace as in real life, politics is always better organised bottom-up than top-down. Thankfully, fifty years after the opening of the 1964/5 New York’s World Fair, the USA’s elite is no longer the exclusive owner of the hi-tech future. The empire’s networked computers have become the tools of its rebellious subjects’ collective emancipation. As the heroic Vietnamese partisans so emphatically proved four decades ago when they successfully breached the McNamara Line, the NSA’s totalitarian technologies may be able to slow down historical progress, but these spooks can’t reverse its direction. Empowered by the Net, the peoples of this planet are engaged in collaboratively building a truly human civilisation. The virtual future is here and now.

Dr Richard Barbrook is Senior Lecturer in Politics at the University of Westminster in London, England and a founding member of Cybersalon. He is the author of Class Wargames: ludic subversion against spectacular capitalism; Imaginary Futures: from thinking machines to the global village; The Class of the New; and Media Freedom: the contradictions of communications in the age of modernity. For more information, check out his websites:

Dr Richard Barbrook is Senior Lecturer in Politics at the University of Westminster in London, England and a founding member of Cybersalon. He is the author of Class Wargames: ludic subversion against spectacular capitalism; Imaginary Futures: from thinking machines to the global village; The Class of the New; and Media Freedom: the contradictions of communications in the age of modernity. For more information, check out his websites:

http://www.imaginaryfutures.net

http://classwargames.net

This article was first published by Die Zeit, you can read the German version here.

Love this site – cheers guys