This is a sort-of summary of Wendy’s Tuesday evening talk at DC4420 – originally published on Net.Wars

Loopholes within loopholes, the EFF called the draft Investigatory Powers bill last November. The bill enshrines a long-held wishlist of policies; in his 2012 submission to the Joint Committee on the draft Communications Data Bill, the late Caspar Bowden said, “The kernel of the CDB was already fully formed in 2000, before the Olympics, national scale rioting, 7/7, Iraq, Afghanistan, and 9/11.” Bowden’s evidence was a leaked National Criminal Intelligence Service submission to the Home Office in 2000, which suggested retaining all “internet-related” data for five years in either a giant national “data warehouse” or in smaller warehouses kept by communications service providers. Then, the estimated cost was £3 million; today it’s £170 million over ten years, as per oral testimony to the Joint Committee in December (PDF), double the present retention regime (Q121).

Loopholes within loopholes, the EFF called the draft Investigatory Powers bill last November. The bill enshrines a long-held wishlist of policies; in his 2012 submission to the Joint Committee on the draft Communications Data Bill, the late Caspar Bowden said, “The kernel of the CDB was already fully formed in 2000, before the Olympics, national scale rioting, 7/7, Iraq, Afghanistan, and 9/11.” Bowden’s evidence was a leaked National Criminal Intelligence Service submission to the Home Office in 2000, which suggested retaining all “internet-related” data for five years in either a giant national “data warehouse” or in smaller warehouses kept by communications service providers. Then, the estimated cost was £3 million; today it’s £170 million over ten years, as per oral testimony to the Joint Committee in December (PDF), double the present retention regime (Q121).

We’ll summarize ten problem areas:

– Secrecy. As George Danezis writes, the bill is liberally sprinkled with gagging orders. It will be impossible to ensure either confidentiality or security.

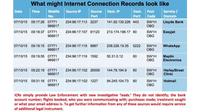

– Internet Connection Records. The bill’s S59(6) definition is claimed to mean “only” metadata, but as Susan Landau, Matt Blaze, Steve Bellovin, and Stephanie Pell explain in It’s Too Complicated (PDF), distinctions between metadata and content are no longer possible. In oral testimony, small ISP owner Adrian Kennard said after a Home Office briefing, “It is so vague that, no, we do not know what it is” (Q120). Paul Bernal suggests ICRs answer the wrong question (“How do we recreate those useful telephone bills?”) and advises asking a better one: “How do we catch terrorists and serious criminals when they’re using all this high-tech stuff?” Bernal also calls the resulting databases “perfect for identity theft”, a point underlined by Big Brother Watch’s recent FOIA request-based report (PDF) showing that police forces were responsible for at least 2,315 data breaches between June 2011 and December 2015. At MIS-Asia, Scott Carey posted the National Crime Agency’s imagining of an ICR data format; perhaps someone believed the Open Rights Group’s 2009 Statebook mock-up is actually possible. In that 2000 leaked NCIS document, Roger Gaspar wrote, “Agreement will be needed to ensure that the provisions of Clause 20, Part 1, Chapter II, Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act can be interpreted as widely as possible to include all Internet related data.”

– Internet Connection Records. The bill’s S59(6) definition is claimed to mean “only” metadata, but as Susan Landau, Matt Blaze, Steve Bellovin, and Stephanie Pell explain in It’s Too Complicated (PDF), distinctions between metadata and content are no longer possible. In oral testimony, small ISP owner Adrian Kennard said after a Home Office briefing, “It is so vague that, no, we do not know what it is” (Q120). Paul Bernal suggests ICRs answer the wrong question (“How do we recreate those useful telephone bills?”) and advises asking a better one: “How do we catch terrorists and serious criminals when they’re using all this high-tech stuff?” Bernal also calls the resulting databases “perfect for identity theft”, a point underlined by Big Brother Watch’s recent FOIA request-based report (PDF) showing that police forces were responsible for at least 2,315 data breaches between June 2011 and December 2015. At MIS-Asia, Scott Carey posted the National Crime Agency’s imagining of an ICR data format; perhaps someone believed the Open Rights Group’s 2009 Statebook mock-up is actually possible. In that 2000 leaked NCIS document, Roger Gaspar wrote, “Agreement will be needed to ensure that the provisions of Clause 20, Part 1, Chapter II, Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act can be interpreted as widely as possible to include all Internet related data.”

– Request filter (S63ff). The claim is that the filter will protect privacy by limiting the data investigators see. It’s possible that implementing it require direct access to third-party databases, a serious security issue. The bill’s Schedule 4 list of the agencies that will have access to communications data can be modified by subsequent regulations (Notes, paragraph 191).

– Request filter (S63ff). The claim is that the filter will protect privacy by limiting the data investigators see. It’s possible that implementing it require direct access to third-party databases, a serious security issue. The bill’s Schedule 4 list of the agencies that will have access to communications data can be modified by subsequent regulations (Notes, paragraph 191).

– Bulk, as in “equipment interference” (hacking) and “personal datasets”. In the June 7 Commons debate on the IPB, it was explained thusly: “Bulk equipment interference is not targeted against particular person(s), organisation(s) or location(s) or against equipment that is being used for particular activities.” So bulk is…”all the phones in the world”? Seeing the note “additional safeguards for health records” next to bulk personal datasets is not reassuring. A couple of days ago, Privacy International published documentsshedding new light on the government’s prior use of bulk datasets.

– Technical capability notices (S226). The clearest problem is the power to require “relevant operators” to remove the electronic protection they’ve applied, taking into account likely cost and technical feasibility. Like the FBI wanted Apple to provide.

– Double lock. It sounds OK: warrants are issued by a Secretary of State but must also be signed by a Judicial Commissioner; a refusal can be appealed to the Investigatory Powers Commissioner. The problem it that it’s so easy to appoint rubber stampers. It’s worth noting former Intelligence Services Commissioner Mark Waller’s oral testimony; admittedly lacking technical expertise, he saw no reason why he needed any (Q4).

– Extraterritorial jurisdiction. A technology company’s nightmare, though future employment prospects look bright for anyone studying international law. Days after last week’s Microsoft vs DoJ ruling, US President Barack Obama proposed a US-UK deal enabling law enforcement to access data stored on each other’s servers. The better solution is likely to reform the cumbersome multi-lateral access treaty (MLAT) procedures that direct arrangements are aimed at bypassing.

– Future scope. In oral testimony, then Home Office minister Theresa May indicated that data retention may extend to coffeeshops offering wifi and private networks (universities, libraries, businesses) (Q269); in Parliament on January 3, she said no communications service provider will ever be too small to be served a notice. The present choice of twelve months’ retention period derives from the statistic that 49% of requests in child exploitation cases ask for data between ten and 12 months old.

– Legal compatibility. In the bill’s notes, May calls the IPB “compatible with the Convention rights”. The Advocate-General of the European Court of Justice disagreed last week with regard to the less-invasive DRIPA. OIf course, Britain may not have to care about conventions in future.

Much of this legislation is “Be the envy of other major governments” precedent-setting powers. Former GCHQ director David Omand underlined this in oral testimony: “This Bill contains the basis of the gold standard for Europe.” (Q79)

IPB isn’t law yet. Those opposing might write your MP, join ORG or Liberty, sign the Don’t Spy on Us petition, or donate to Privacy International.

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard – or follow on Twitter.