Originally posted on pelicancrossing.net on August 4th, 2017

I learned something new this week: I may not be a real person.

“Real people often prefer ease of use and a multitude of features to perfect, unbreakable security.”

So spake the UK’s Home Secretary Amber Rudd on August 1, and of course what she was really saying was, We need a back door in all encryption so we can read anything we deem necessary, and anyone who opposes this perfectly sensible idea is part of a highly vocal geek minority who can safely be ignored.

The way I know I’m not a real person is that around the time she was saying that I was emailing my accountant a strongly-worded request that they adopt some form of secured communications for emailing tax returns and accounts back and forth. To my astonishment, their IT people said they could do PGP. Oh, frabjous day. Is PGP-encrypted email more of a pain in the ass than ordinary email? You betcha. Conclusion: I am an imaginary number.

According to Cory Doctorow at BoingBoing’s potted history of this sort of pronouncement, Rudd is at a typical first stage. At some point in the future, Doctorow predicts, she will admit that people want encryption but say they shouldn’t have it, nonetheless.

According to Cory Doctorow at BoingBoing’s potted history of this sort of pronouncement, Rudd is at a typical first stage. At some point in the future, Doctorow predicts, she will admit that people want encryption but say they shouldn’t have it, nonetheless.

I’ve been trying to think of analogies that make clear how absurd her claim is. Try food safety: >>Real people often prefer ease of use and a multitude of features to perfect, healthy food.>> Well, that’s actually true. People grab fast food, they buy pre-prepared meals, and we all know why: a lot of people lack the time, expertise, kitchen facilities, sometimes even basic access to good-quality ingredients to do their own cooking, which overall would save them money and probably keep them in better health (if they do it right). But they can choose this convenience in part because they know – or hope – that food safety regulations and inspections mean the convenient, feature-rich food they choose is safe to eat. A government could take the view that part of its role is to ensure that when companies promise their encryption is robust it actually is.

But the real issue is that it’s an utterly false tradeoff. Why shouldn’t “real people” want both? Why shouldn’t we *have* both? Why should anyone have to justify why they want end-to-end encryption? “I’m sorry, officer. I had to lock my car because I was afraid someone might steal it.” Does anyone query that logic on the basis that the policeman might want to search the car?

The second-phase argument (the first being in the 1990s) about planting back doors has been recurring for so long now that it’s become like a chronic illness with erupting cycles. In response, so much good stuff has been written to point out the technical problems with that proposal that there isn’t really much more to say about it. Go forth and read that link.

There is a much more interesting question we should be thinking about. The 1990s public debate about back doors in the form of key escrow ended with the passage in the UK of the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (2000) and in the US with the gradual loosening of the export controls. We all thought that common sense and ecommerce had prevailed. Instead, we now know, the security services ignored these public results and proceeded to go their own way. As we now know, they secretly spent a decade working to undermine security standards. They installed vulnerabilities, and generally borked public trust in the infrastructure.

So: it seems reasonable to assume that the present we-must-have-back-doors noise is merely Plan A. What’s Plan B ? What other approaches would you be planning if you ran the NSA or GCHQ? I’m not enough of a technical expert to guess at what clever solutions they might find, but historically a lot of access has been gained by leveraging relationships with appropriate companies such as BT (in the UK) and AT&T (in the US). Today’s global tech companies have so far seemed to be more resistant to this approach than a prior generation’s national companies were.

This week’s news that Apple began removing censorship-bypassing VPNs from its app store in China probably doesn’t contradict this. The company says it complies with national laws; in the FBI case it fought an order in court. However, Britain’s national laws unfortunately include 2016’s Investigatory Powers Act (2016), which makes it legal for security services to hack everyone’s computers (“bulk equipment interference” by any other name…) and has many other powers that have barely been invoked publicly yet. A government that’s rational on this sort of topic might point this out, and say, let’s give these new powers a chance to bed down for a year or two and *then* see what additional access we might need.

This week’s news that Apple began removing censorship-bypassing VPNs from its app store in China probably doesn’t contradict this. The company says it complies with national laws; in the FBI case it fought an order in court. However, Britain’s national laws unfortunately include 2016’s Investigatory Powers Act (2016), which makes it legal for security services to hack everyone’s computers (“bulk equipment interference” by any other name…) and has many other powers that have barely been invoked publicly yet. A government that’s rational on this sort of topic might point this out, and say, let’s give these new powers a chance to bed down for a year or two and *then* see what additional access we might need.

Instead, we seem doomed to keep having this same conversation on an endless loop. Those of us wanting to argue for the importance of securing national infrastructure, particularly as many more billions of points of vulnerability are added to it, can’t afford to exit the argument. But, like decoding a magician’s trick, we should remember to look in all those other directions. That may be where the main action is, for those of us who aren’t real enough to count.

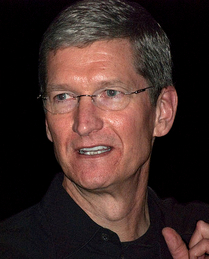

Illustrations: The Virgin Mary punching the devil in the face (book of hours (‘The De Brailes Hours’), Oxford ca. 1240 (BL, Add 49999, fol. 40v), via Discarding Images); Amber Rudd; Tim Cook (Valery Marchive).

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard – or follow on Twitter.