On so many sides, in so many ways, the sale of .org is a tangled thicket of stakeholder unhappiness. There seem to be six major categories of complaints: sentimental, financial, practical, structural, ethical, and paranoid.

First, some background. The domain name system of which .org is a part was devised in the mid-1980s by Paul Mockapetris. Even though no rules limit registrations in .org, the idea that it is used by non-commercial organizations persists. In 1997, as the Internet was being commercialized, the original one-man manager, John Postel, was replaced by the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, which manages the network of registries (each manages one top-level domain) and registrars (which sell domain names inside those TLDs). At the same time, the gTLDs were opened up to competition; the change led in 2002 to .org‘s being handed off to the Internet Society-created, non-profit Public Interest Registry. Six months ago, the Internet Society announced that PIR would drop its non-profit status; two weeks ago came the sale to newly-formed Ethos Capital. Suspicious minds shouted betrayal, and the Nonprofit Technology Enterprise Network promptly set up SaveDotOrg. Its nearly 13,000 signatures include hundreds of NGOs and Internet organizations.

At The Register, Kieren McCarthy – the leading journalistic expert on the DNS and its governance – laid out what little was known about the sale and the resulting conflict. He followed up with the silence that met the complaints; the discontent on view at the Internet Governance Forum; an interview with ISOC CEO Andrew Sullivan, who said “Most people don’t care one way or another” and that only a court order would stop the sale; and finally the news that the opportunity to sell PIR came out of the blue. Late on, the price emerged: $1.14 billion. Internet Society says it will use the money to further its mission to promote the good of the Internet community at large.

So, to the six categories. The Old Net remains sentimentally attached to the idea of .org as a home for non-profits such as Internet infrastructure managers IETF and ISOC, human rights NGOs ACLU, and Amnesty International, and worldwide resources Wikipedia, the Internet Archive, and the Gutenberg Project. But, as the New York Times comments, this image of .org is deceptive; it’s also the home of the commercial entity Craigslist and dozens of astroturf fronts for corporate interests.

At Techdirt, Mike Masnick traces the ethics, finding insider connections. The slightly paranoid concerns surround: the potential for the registry owner to engage in censorship. The practical issue is the removal of the price cap; an organization with a long-time Internet presence can in theory simply register a new domain name if the existing one becomes too expensive, but in practice the switching costs are substantial, and we all pay them as links break all over the web. A site like Public Domain Review could be held to ransom by rapidly rising prices. Finally, the structural concern is that yet another piece of the Internet infrastructure is being sold off to centralized private interests who will conveniently forget the promises they make at the time of the sale.

The most interesting is financial: New Zealand fund manager Lance Wiggs thinks ISOC is undercharging by $1 billion; he also thinks they should publish far more detail.

Most of Wiggs’ questions remained unanswered after yesterday evening’s community call organized by SaveDotOrg and NTEN. The question-answering session included Sullivan, Ethos CEO Erik Brooks, Ethos Chief Purpose Officer Noral Abusitta-Ouri, EFF attorneys Mitch Stoltz and Cara Gagliano, PIR CEO John Nevin, and ISOC Ireland head Brandt Dainow.

Sullivan said both that there were other suitors for PIR and that because speed was of the essence to close the deal it was necessary to negotiate under non-disclosure agreements. The EFFers were skeptical. The Ethos Capital folks sprayed reassurances and promises of community outreach, but were evasive about nailing these down with binding, legally enforceable contracts. Least impressed was Dainow, which shows there’s disagreement within ISOC itself. I’m no financier, but I do know this: the more you’re pressured to close a deal quickly the more you should distrust the terms.

To some extent, all of this is a consequence of the fundamental problem with the DNS: we have no consensus on what it’s for. This was already obvious in 1997, when I first wrote about it. Then, as now, insiders were enraging the broader community by making deals among themselves without wider consultation – a habit agreed principles and purposes could constrain. In 2004 I asked, “Does it follow geography, trademarks and company names, or types of users? Is it a directory or a marketing construct? Should names be automatically guessable? What about, instead, dividing up the Net by language? Or registered company names, like .plc.uk and .ltd.uk? Or content, like .xxx or .kids? Why not have an electronic commerce space where retailers register according to the areas they deliver to?” None of these is more obviously right than another, but as long as there are no agreed answers, disputes like these will keep emerging.

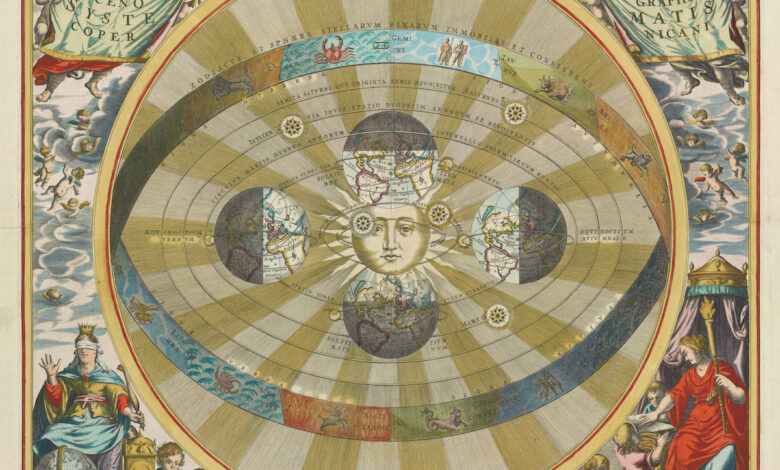

Illustrations: Copernican map of the universe (from the Stanford collection, via Public Domain Review).

Wendy M. Grossman is the 2013 winner of the Enigma Award. Her Web sitehas an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard – or follow on Twitter.