Digital Citizenship: from liberal privilege to democratic emancipation

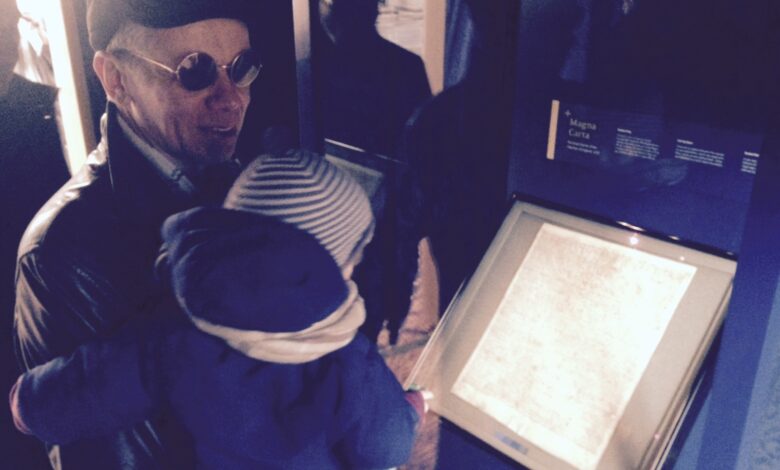

On the anniversary of the Magna Carta, Richard Barbrook calls for a new debate on the conception of citizenship.

‘Government founded… on a system of universal peace, on the indefeasible hereditary Rights of Man … interests not particular individuals, but nations, in its progress, and promises a new era to the human race.’

– Tom Paine, Rights of Man

In the second decade of the 21st century, citizenship is defined not just by the people being able to choose the political leadership of their nation through regular elections, but also by the legal protection of their human rights, such as media freedom, personal privacy, fair trials and religious toleration. Enshrined in both national constitutions and international treaties, these democratic precepts ensure that individual citizens can express their views and campaign for causes without fear of persecution or discrimination. Yet, when they were first codified during the 17th and 18th centuries’ modernising revolutions which overthrew aristocratic and priestly despotism in Western Europe and North America, these fundamental freedoms were initially restricted to a minority of the population: white male property-owners. Despite the universalist rhetoric of the English 1689 Bill of Rights, the French 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen and the USA’s 1791 Bill of Rights, men without property, all women and the African slaves who were property remained outside their constitutional protection. In this pioneering liberal iteration, political and civil freedom was founded upon economic exploitation. Human rights were the privilege of the few not the emancipation of the many.

Over the past two centuries, this oligarchic interpretation of citizenship has been superseded by a more democratic vision of individual liberty. Adopted in the immediate aftermath of the victory over fascism, the United Nations’ 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the 1950 European Convention on Human Rights included the previously excluded within their provisions. All adults were now entitled to the full rights of political citizenship. When these mid-20th century charters were being drawn up, there were fierce debates between Left and Right over whether social and economic rights should also be given legal recognition. Seeking to mobilise the masses against its internal and external enemies, the Jacobins had promised in their 1793 Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen that the French republic would ensure that all citizens had access to the necessities of life. In 1944, responding to the global wartime emergency, US president Franklin Roosevelt had called for a new bill of rights which guaranteed employment, housing, healthcare, education and pensions for the whole population. Although the Right vetoed their inclusion in the 1948 and 1950 charters, the Left’s socio-economic precepts of human liberty were eventually codified in the United Nations’ 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Individual freedoms required the collective means to realise them in practice. The liberties of the many must take precedence over the privileges of the few.

During the past few decades, this socialist version of human rights has been almost forgotten. For the Left as well as the Right, the implosion of the Soviet Union has justified a return to the original liberal interpretation of these constitutional principles. According to the USSR’s 1936 Fundamental Rights & Duties of Citizens, every adult was entitled to an impressive collection of both political-civil and socio-economic freedoms. Unfortunately, as anyone who tried to put them into practice soon discovered to their cost, these emancipatory promises had been devised as ideological mystifications. By emphasising social and economic rights over political and civil liberty, the Stalinist dictatorship could deny both types of citizenship to its citizens. Not surprisingly, many of those who opposed this totalitarian regime concluded that the Left’s attempts to extend human rights into civil society had negated their original intention: protecting individual freedom from state tyranny. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the demise of Stalinism in Eastern Europe and Russia was symbolised by their new democratic governments’ enthusiasm for the 18th century interpretation of personal liberty. The USA’s 1791 Bill of Rights didn’t need augmenting by the UN’s 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. On the contrary, political and civil freedom from state interference was the only possible form of freedom in the post-modern world. Liberalism and democracy were synonymous.

The recent revelations by Edward Snowden and other whistle-blowers about the American empire’s megalomanic scheme to spy upon every inhabitant of the planet have discredited the West’s self-identification as the global champion of human rights. Even with their huge resources, the Stalinist spooks of the KGB with their 20th century industrial technologies were only able to monitor the activities of a minority of Soviet citizens. In contrast, the NSA is now equipped with 21st century digital technologies which can intercept the emails, texts, phone calls, web browsing, media downloads and social media activity of almost all of humanity. Most worryingly, the liberal guarantees of the 1791 Bill of Rights have failed to protect the American people from the totalitarian ambitions of their own nation’s secret police. Added as the 4th Amendment of the US constitution, a clause of this charter promised that the private communications of individual citizens could only be intercepted in exceptional circumstances which required judicial authorisation. However, this fundamental principle was quickly discarded to reassure an American public terrorised by Al Qaeda’s 2001 murderous attacks on New York and Washington DC. Having obtained the approval of a supine legislature and compliant courts, the US government ordered the NSA to build the technical infrastructure for the ubiquitous surveillance of the entire global population. Like its defunct Stalinist rival, the American empire now champions the ideal of individual freedom to negate its implementation in practice. Far from advancing political and civil rights, the abandonment of socio-economic rights has emboldened the imperial hegemon to eviscerate all legal restrictions on its repressive powers at home and abroad. National security is now the antithesis of personal liberty.

The NSA’s totalitarian project to place the whole of humanity under permanent real-time surveillance is built upon the dominance of corporate America over the Net. Whether for targeted advertising, market research or customer relations, these dotcom companies have become proficient at gathering and analysing data about how people are using their products and services. From social media postings to on-line shopping, people are constantly sharing intimate details of their private lives with strangers. For the NSA’s spooks, gaining access to this confidential information which can reveal an individual’s political opinions, moral beliefs and cultural tastes is a top priority. Since anyone could be an enemy of the American empire, everyone on this planet is a target of surveillance. According to some clever hackers and resourceful entrepreneurs, this illegal snooping can be thwarted by developing strong forms of encryption for the masses. However, as revealed by Snowden’s leaks, any technological fix is unlikely to provide a long-term solution for protecting personal privacy. It isn’t just that the NSA has become adept at breaking encryption by compromising software and hardware security. Above all, the 18th century’s concept of a citizenry composed of atomised individuals is an anachronism for the 21st century’s networked masses. What was once revolutionary has now become reactionary. At the dawn of modernity, liberalism emerged as the philosophy of the white male property-owners who challenged monarchical oppression and clerical bigotry. With capitalism now in its dotage, the boosters of neo-liberalism have appropriated this radical heritage to excuse the social and environmental depredations of corrupt governments, fraudulent banks and tax-dodging corporations. By praising political-civil rights to demonise socio-economic rights, these apologists of the American empire have undermined the juridical foundations of both types of citizenship. The defence of liberal democracy against Stalinist tyranny has morphed into the advocacy of neo-liberal oligarchy against plebeian democracy.

At this dangerous moment in the history of humanity, personal freedom is threatened by the intrusive attentions of both authoritarian states and monopolistic businesses. If liberty and democracy are to be enhanced within the Net, what is now required is an energetic public debate over how to construct a new constitutional settlement which nurtures today’s collective forms of digital citizenship. In the virtual world as in real life, people must be confident that not only their personal communications will remain private, but also they can freely express controversial opinions without inhibition. Crucially, these political and civil rights must be combined with socio-economic rights. The sharing of information over the Net is a premonition of the democratisation of the whole productive process. If they are to contribute to this collaborative endeavour, everyone must have access to the knowledge and technologies which will be used to build the emerging network society. Like its liberal and socialist predecessors, this new dispensation should be guided by its own rules of the game. The creation of a Net Bill of Rights codifies the mutually agreed principles for regulating individuals’ on-line activities in the common interest. By collectively defining a new vision of digital citizenship, this generation can make its own world-historical contribution towards building a truly human civilisation. The better future must be anticipated in the troubled present. Let’s seize this opportunity to transform our utopian dreams into everyday life!

Richard Barbrook,

8th March 2015,

London, England.

Thanks on your marvelous posting! I genuinely enjoyed reading it, you are a

great author.I will always bookmark your blog and definitely will come back someday.

I want to encourage one to continue your great job,

have a nice evening!

I came from twitter well done on an excellent social media

campaign