Afrofuturism – Reclaiming Cyberspace

Jaron Lanier, the inventor of Virtual Reality noted that “who owns the future owns the presence” pointing at the magic power of futuristic imagery. If you can imagine it, if you can will it into existence, your vision will happen. To celebrate the transformative power of Afrofuturism in sci-fi literature and movies, on 20th October Cybersalon.org held a virtual event discussion with Douglas Rushkoff (TeamHuman.fm), David Bering-Porter (Race and Ethnicity professor) from The New School, Paul Miller aka DJ Spooky and Derek Richards, musician and composer from HyperJAM/Artec, chaired by Eva Pascoe (Cybersalon.org). Watch the event here

What is Afrofuturism?

The history of Afrofuturism dates from Sun Ra, a musician and visionary leader who created the Arkestra music ensemble – in a reference to the myth of Noah’s ark and a vision of leading his people out of this planet to explore a better life in Outer Space. He co-produced the movie Space is the Place (1974) where he played the tribe’s elder, investigating a new planet ‘with a better vibe’, where his people could find more of a conducive environment to find love and happiness. The set is a mix of fantasy, space faring with elements of the Pharaoh’s insignia as head decoration, riffing on time travel from an Egyptian past when the African continent led the world in knowledge. Sun Ra is on a journey to discover a new planet and to re-create a better life for his people.

David Bering-Porter (The New School) noted this dream of liberation occurs in Afrofuturism as one it it’s key themes. It is imagining “culture from the margins”, using fantasy for the productive means of creating a new identity and roadmap to different, more inclusive future worlds. One mystery was the reason why Sun Ra chose the Pharaoh’s era as a context for his fantastic explorations, as Egyptian society was based on slavery as a base for their labour arrangement.

Eva Pascoe noted similar themes emerging in TheArchAndroid tale in Janelle Monae’s (2010) record about a messianic android sent back in time to free the citizen of fictional (but recognisable American city) Metropolis, to bring freedom and love. The ArchAndroid is the mediator between the haves and have-nots, the minority and the majority. The song is an anthem and inspiration for breaking out of confinement and bringing empowerment and growth.

Sci-fi author Tade Thompson (British Yoruba) makes a point for seeking alternative histories in space travel. In his book, of bio-punk genre “Rosewater”, aliens conquer planet Earth and swallow London, but choose to offer healing and ‘raising the dead’ contribution https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/tade-thompsons-rosewater-an-alien-invasion-that-grows-on-you/, with more nuanced relationships than just to capture and enslave the Earthlings.

Afrofuturims continued growth during in 70ties but was only defined by Mark Dery in 1993 in his essay Black to the Future. He conceptualised it not as a united movement but a creative trend to re-imagine alternative futures through the lens of an AfroAmerican perspective.

As David Bering-Porter noticed, it is also a process of retrieval, looking for alternative personas, learning how old identities were created and how can they reclaim the narrative, project into the future and reclaim cyberspace.

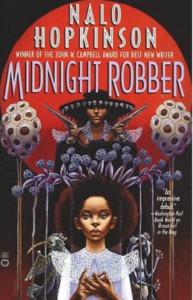

Techno-culture was on the rise in mid 90ties and gave rise to a number of different re-visioning, building on the previous sci-fi writing of Olivia Butler, Nalo Hopkinson (Midnight Robber) , preparing the ground for the more contemporary Tade Thompson (Rosewater).

Connecting the Nodes

Derek Richards (HyperJAM and founder of Artec), one of London’s techno-culture pioneers, pointed out that in early Internet experiments in the 90ties, connecting musicians in real time in New York (Kitchen) and London (Café Cyberia, clubs like Metropolis) were attracting new audiences. There were grabbing attention as people were looking for new meaning in cyberspace, looking to join hands virtually and build new networks to find strengths in togetherness, to challenge unsatisfactory reality.

Using new connectivity was empowering, helping to see cyberspace as a world of great possibilities, where only imagination is the limit. HyperJAM was involved on the way in co-creating in virtuality, with pioneers, where member of the settlers group had a unique opportunity to grab this new emerging technology frontier and put diversity into the DNA of the emerging new pixelscapes.

Digital Slam and virtual networking transatlantic events led by Mark Boothe, with works by Gary Stewart, Keith Piper and many others built a foundation for a pluralistic vision of future digital worlds.

Re-birth of a Nation and DJ culture mix

Afrofuturism is also defined as an art practice focused on examining current constraints and finding ways of overcoming them, using everyday black experience as a jump to thinking out how extrapolation of today’s ways of life may play out in alternative future societies. As DJ Spooky aka Paul Miller (NYC) noted, unlike India, America is not confined to cast system. Identities can be re-negotiated and are not locked into immovable social structures. He also pointed out that modern history is attributing the beginnings of science and knowledge to Greeks, but a significant number of inventions were already in place in Egypt, then re-discovered and re-developed by Greek scholars on the foundations developed by earlier African civilisation.

Paul uses the privilege of DJs to remix logic, with Afrofuturism deployed as a medium for re-telling the stories (as he did remixing Birth of the Nation, into Re-birth of the Nation and projecting it in Acropolis in Athens, using concepts like Black Athena, on location noted as the origin of Western culture).

VR goddesses-engineers

AfroFeminist futures are explored by Hyphen-Labs, a VR/design collective speculating on the future by designing VR worlds built on female experiences and with women as hosts. The piece has emerged from thinking about the importance of hair salons for black women. It’s VR journey starts with me sitting in a real hairdressing chair, but by putting on the headset it moves the participants into virtual beauty salon. This is where brain modulation is applied to change the perspective of the participant on race and life with minorities. A giant cathedral-like environment encourages exploration by a virtual boat with eventual arrival to a temple, hosted by women-engineers, godess like. Neuromodulation is a methaphor for social change and re-creating a new world of equality and inclusivity by design.

Hyphen Lab has also investigated women’s needs while facing technology, creating a scarf that deflects facial recognition cameras to avoid being captured and locked in a dataset that may be used against you.

Another product reflecting on women’s need for self-defence is a pair of earrings that record what is happening, which can act as a ‘witness’ in case of someone being threatened with violent behaviour. Unlike creatives from Sun Ra to Monae which create inspirational utopias, Hyphen Lab pieces are anchored in urban dystopia , providing designs for a city immersed with the risk of techno-surveillance and violence. Their VR world is more optimistic, with neuro-modulation envisaged as a constructive way of changing prejudice and biased perceptions. Fusion of sci-fi, design and fantasy produce thought-provoking conversation pieces – products not for everyday use but everyday discussion.

Such an approach of using technology for social good is underpinning urban activism, with Ingrid La Fleur running for Mayor in Detroit on an AfroFuturist ticket. She proposed to re-imagine Detroit using the technology of today but also commissioning tech we haven’t got yet to solve contemporary problems.

Afrofuturism in Zambia

Having futuristic goals helped to change the perception of Africans in real space travel program. In the early 60ties in Zambia, a young science teacher initiated the Zambian Space Program, devising a training that was based on the Russian cosmonauts academy. Eva Pascoe told how she discovered the history of this program while living in Zambia in the early 80ties. The program in Zambia lasted only a few years and struggled with funding, but Zambia has recalibrated it’s science goals and has been an early trendsetter building a solid medical science teaching program at Lusaka University, initially staffed by Eastern European scientists, then handing over to Zambian engineers and scientists.

The program has later influenced the recruitment of Afroastronauts in US, with the first African Americans selected for space training in early 1978, the cohort staffing some of the most complex missions of the entire space research program.

Openess of Techno-Culture of the 90s

The current digital constraints are noted by Derek Richards, pointing out that 90ties technoculture was about openness, with everyone able to participate and put a webpage or digital jam up. No investment was needed to get a digital audience, people would follow on forums and find each other without advertising budgets.

In contrast, today, we are battling with constraints and digital tolls imposed by the 4 monopolies of the digital economy, Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple.

Douglas Rushkoff (author of cyberpunk novel Cyberia) also noted that the spirit of the 90ties Internet culture emerged out of earlier psychedelia, hypertext and that connecting diverse concepts was the prevailing more of creative experiments. When the early digital pioneering started transforming to a more commercial Internet, technoculture gave way from creative to extractive, from artistic to neoliberal philosophy, led by Wired magazine (editor Louis Rosetto) and hijacked by big tech technology vendors like Adobe, Intel and Sony.

For Rushkoff, Afrofuturism is a journey of retrieval, of re-learning the past to cope with or current, globalised future. He notes that the early Internet was “blind” to race and gender, as it was based on text, mostly image free due to bandwidth constraints therefore skin colour or gender was not an attribute anyone noted.

The famous saying ‘On the Internet nobody knows you are a dog” (cartoon from The New Yorker) was true as the early Internet gave us an opportunity to call minorities to participate equally in the building of technocultures. It was like Year Zero, re-setting the button on this new medium, overcoming the limitations of print or TV.

Early bulletin boards like The Palace, Usenet, or Echo NY – Stacy Horn arty only bohemians of the 90ties of which we were all members were diverse. Cyberia Café carried this open door policy in the physical Cyberia Café and our connected agencies like Cyberia Music, later to Cyberia Cafes in other cities like Tokyo and Bangkok.

Unfortunately, the Internet was not like TV, and did not have protection against tribalisation. Douglas Rushkoff notes that instead of all of us being a ‘Node on the Network’, the network split in to thousand factions, echo chambers, inward looking and, more importantly, fighting against each other.

We have learned that globalisation is de-segmenting, not unifying. This atomisation of small, interest -led groups can however be re-built as Douglas argues, we are all ‘Gaians’ . Our purpose is to continue the successful journey of humanity on Earth, avoiding self-destruction and therein we must seek common ground, unify to adjust our lifestyles to ensure survival and avert eco-catastrophy. Retrieval of indigenous cultures’ ways of co-existing with their surroundings , learning from them, is one of the areas where Rushkoff argues we need to explore.

Data Colonialism versus digital creativity

As we move discussion to data and the impact of a new power structure with Digital Monopolies, Derek Richards notes that colonialism is alive and kicking with big tech stealing our personal data, creating avatars of our Digital Personas and enslaving them in the matrix. Millions of young black musicians spend hundreds of hours creating music for You Tube, Facebook or Instagram completely for free, for no reward at all.

Google and Twitch has turned young musicians and young gamers into gamblers, who give up paid work to spend hours posting free content, commenting on Twitch games, lives streaming and hoping to make millions. In fact, this is a myth, debunked many times by Dr Alexandro Gandini and others. Less than top 1% of ‘creators’ actually earn any income, and less than 0.1% make a living out of their creative efforts.

As Derek argues, not satisfied with claiming time and the talents of young creators, Digital Platforms like YouTube and Twitch also steal and manipulate their political personas.

Cambridge Analytica perfected the art of micro-marketing and political manipulation online, hijacking not just creative talents but our votes. Retrieving the past and reclaiming our identities to prevent exploitation is hard but necessary work for shaking off the chains of digital colonialism both for ethnic minorities and mainstream participants, notes Derek.

Urban Afro Futurism

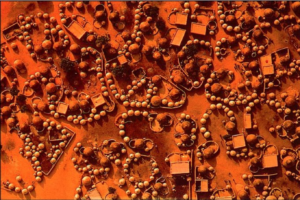

Paul Miller points to work of Ron Eglash on revaluating the patterns like Fractals. Their use is connected to Mandelbrot and early digital psychodelia aesthetics, but in fact fractals are a base of village designs in traditional African architecture. They are also present in hair-braiding styles and fabrics.

The concept of a “grid” for cities had not been developed till Greek proto-architect Hippodamus (father of urban planning that you will know from New York grid structures), while organic fractal patterns of nature were traditionally followed in Africa where scaling up of a settlement was needed, going back to the earliest settlements – a practice that contemporary African architects are reviving.

Today futuristic discussions about the visual shape of fast growing African cities are focusing on the dichotomy of importing efficient but essentially foreign urban designs from Singapore-based architects, or alternatively, seeking local architects who will bring in local knowledge of materials, patterns and interpret local, Afrofuturistic visions. Searching to renew cities by revolutionary architecture is a process that had a storming success for Centre Pompidou in Paris to build on – it’s famous inside-out, modernist design, was a sign to the old regime that a new, younger, fresh culture of the 70’s generation was taking over Paris.

Are we still centralising or diverging?

Simon Sarginson (Cybersalon.org) asked during the discussion if we feet that technology is still pushing us with centripetal or centrifugal forces? Is Big Tech bringing us together or tearing us apart and is Afrofuturism likely to benefit from those forces.

Douglas Rushkoff responded that digital revolution is likely to happen locally, pushing against digital platforms and the values of Big Tech. But any successful push and successful changes must be replicated in the Network, so in some sense the forces are both local and global.

The danger is that we have no experience with dealing with such huge monopolies like Google, Facebook, Amazon or Apple and we have not archive of responses, of mental vaccines, or techniques how to protect ourselves. Misinformation, fake news and manipulation of digital personas are creating a real danger for fascism and totalitarian regimes to thrive on, with a huge risk to ethnic minorities but also to mainstream political participation.

Access to Web 2.0 has also been restricted as compared to Web 1.0. Migration to Facebook/Instagram. David Baring-Porter notes that the big tech gatekeepers to the Web and the proprietary nature of mobile phones has created a major loss of control over the content and vulnerability to hijacking of the message.

Stephen Oram, sci-fi writer and educationalist raised the question on what we can learn about the direction of digital media and impact from a TV perspective. Rushkoff noted that the current lockdown ‘overdose’ of Zoom, Facebook and general excess of exposure to digital media may turn people off digital as his Father turned him off smoking by making him smoke a whole packet of cigarettes at once.

Douglas’s view is that “we are all so disgusted with digital life” that rediscovery of physical neighbours, physical community may come naturally, helping to re-commune with your fellow humans.

Paul Miller adds his concerns ”if we are going to even make it out of this century”, struggling with impending eco-catastrophe. It may have been informed by his location, as Paul was participating in the event from his house in Colorado in the mountains, surrounded by fire that has been coming dangerously close to his house!

He notes that Afrofuturism may be a good lens for renewal and re-engagement with alternative perspectives on relations with the planet and the environment on the micro-scale.

Douglas agreed that local perspective and ‘small, personal scale’ may help with the transition to large scale changes- starting from mutualism, cooperatives, rebuilding of inner cities businesses to create strong financial nodes. He recommends a book on Collective Courage and alternative economic cooperation, based on original black business structures.

Eva noted that in Nalo Hopkinson’s sci-fi thriller Midnight Robber, there is an example of hidden pedi-cab drivers on another planet, forming a Sou Sou collective, based on informal Credit Union arrangements popular amongst the Caribbean community in New York in the 80s and in West Africa.

Douglas argues that the real vanguard may be in going back and retrieving those early, successful mutual cooperatives formats that were later suppressed by McCarthyism persecution and only functioned via the underground financial networks of Churches and Schools.

In response, David Baring-Porter adds that ‘it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism’. Alternative economic models may be tempting and worth retrieving, but we need a solution now not in 50 years.

In conclusion, David noted that at it’s best, Afrofuturism allows us to open space to consider doing things really differently, but at it’s worst, it is a commodified version of that (in reference to Black Panther).

Dr Richard Barbook (Westminster University) agreed, noting that Jefferson’s democracy was built on labour relationships based on free trade in humans and we need to face up to it to move forward and start radical re-thinking of digital democracy for the future.

He notes that on his visit to Jefferson’s estate Monticello, as a child, he got to observe the ‘dumb waiter’ installed to move dinner from Jefferson’s slave servants quarters below the main house and to transport up wine from extensive cellars – a trick Jefferson implemented to dissociate himself from his condition as a slave owner.

In his essay penned in the mid 90ties titled Californian Ideology and other writing Dr Barbrook notes that exploitation of persons thru exploitation of their personal data practiced by Big Tech today is just an extension of the original economic labour framework that Jefferson would have been familiar with.

The new digital citizen is a person whose data belong to them and to them only, including the rights to their face against Facial Recognition cameras – the framework for the digital futures that we need to reclaim.