Collaboration from Games for Good 3.0 – Tend And Befriend Games

29th January 2020

Last decade will be condemned as a total failure of humanity to work together. We may not complete the next decade as human society unless we work together. Climate change and other challenges bring problems that can only be solved by collaboration. We organised this event to o on a journey and examine how to skill up to collaborate better, from passing weapons, providing covering fire in a fight, healing others or boosting a teammate over obstacles.

We are all in it together – collaborate or die

Eva Pascoe (Cybersalon)

Poor handling of global refugee crises, Brexit debacle and complete failure of progress on climate change show us humans as deeply incompetent collaborators. We can’t event act well together under major emergency such as Jan 2020 bushfires in Australia. Our leaders divide us rather than unite, with divide-and-conquer populism in China, Russia, USA, UK, Poland, Hungary and too many others to mention. In response, we have to self-organise, get our act together, learn to be agile in groups and collaborate to fend for ourselves as societies, communities and neighbourhoods.

Games could be our salvation. With gaming time up from 5.6 hours per week to 7.1h on the average, and from 6.51 to 8.21 hours for 26-35 year olds, it is clearly the right medium to practice how to collaborate and work together, remotely as well as physically.

A quick glance into ancient history shows that Greeks valued collabs, with Athena, goddess of wisdom, games & collaboration, serving also as a patron of war gaming and games as skills training tool. In Greek, the word for collaboration is ‘synergasia’ , which has a wider meaning of cooperation but also contribution, where sometimes, one does not get out as much as one put in, but the task is still worth doing for the good of our community.

Clever Athena is also a goddess of Cities, which often demonstrate better collaboration under stress of natural disasters than whole nations.

Collaboration is a marathon rather than sprint- it needs prep like identifying common goals as without clarity nothing happens. Collab partners need a jointly developed structure and which responsibilities are shared and how. Our framework has to be clear on shared responsibility but also who is the person ultimately responsible, where the buck stops.

We need clear authority, mutually agreed, and accountability for achieving agreed goals.

The most important is sharing not only of s resource but also rewards, nobody gets up in the morning unless there is a clear gain in sight (it does not need to be monetary, can be status achievement or unlocking more resource but it needs to be crystal clear and agreed in advance for all collaborators).

In conclusion, collaboration is a complex skill. This complexity was well understood by the ancient Greeks but is less appreciated by modern work practice. It pays to take time to structure collaborations well and be crystal clear on goals, accountability and rewards, as we have learned the hard way during our own experiences of running Games Cooperative Digital Liberties.

Playing “Stardew Valley”

Karolina Janicka (Cybersalon)

Stardew Valley is a simulation game, which leverages community and collaborative village life. You can achieve things by yourself but you move faster if you collaborate. The game prompts the aspect of reflection on your own, personal experiences of living in a big city versus village life. It is quite a sticky game, showing that success is in keeping daily routine of spending morning on watering plants, feeding chickens, seeing your neighbours. It gives a structure to your day more than normal, frantic working day in the big city as we experience today. It does make you question your own daily routines. It forces you to consider if chatting to your flatmates in the morning may be better than going on Instagram or Facebook to chat to remote people who may or may not be your real friends.

Also, for Karolina the big draw of the game was the sense of inclusivity, expressed in many tools and options of all skin shades with the option that you can pick for your skin colour. In Stardew Valley Karo has also rediscovered her rural roots, where village life and farm, picking parsnips for dinner gives the rhythm for your day. It offers a sense of harmony with your environment and gives feeling of achievements for being consistent in your routines of caring for animals, plants and your neighbours. Collaboration is about doing little and often, forming networks and support chains.

Karo described the game experience, pointing out where it is tapping to the sense of something missing, questioning modern humans if there is something more out there than your daily office rat race. She pointed out that Millennials in particular get lost in the big city, where everybody is busy but somehow very little is accomplished. Buzz replaces substance, speed replaces real progress.

The game shows that you that in the office you are working, resting, working, resting and occasionally get terminated. You get to question this status quote, if this is enough, and if the answer is no, then you quit your office job in the game and move to the farm to start a new life. You start on a massive field, lots of territory, and you have to figure out how to get your resources to farm it from scratch.

Karolina points out this is an endurance game, a marathon not a sprint, with collaboration taking time to set, prepare and make successful. Learning how the gifting economy works, the game reveals the collaborative aspects from the beginning. Joining the community and playing your part feels wholesome. The game encourages the building, some quite complex with a lot of detail, like where the roof keeps collapsing. But you can swap weeds for help in roof building with your neighbour, if you don’t know how to progress. The community will help you to pick the right tools, to prioritise tasks and will prompt you when you get stuck.

The sense of achivement is in overcoming difficulty. The game teaches that the progress you can make is much faster if you bunch together, it comes to fruition in the smallest of task.

The game offers escape from daily city grind but also insights of how to work together. Karolina ends up encouraging all to have a go and experience the slow unrolling of the collaborative live on the Stardew Valley farm.

Eliza (by Zachtronics) and Tacoma (by Fullbright) – reviewed by Simon Sarginson

Wellness in games and Self-care – what does it mean to care for others?

As we established that collaboration requires empathy as a core building block of working together. Empathy and what does it mean to care for others is explored in two games that Simon Sarginson is presenting.

First “Tacoma” – simulation game set aboard a seemingly empty space station in 2088. You can interact with objects, that means it is a physical simulation, shoot balls, darts, balls, a physical simulation. You can’t interact with people. This feels odd. The game follows up from previous Fullbright game. The player character my, has an AR device that allows her to review actions and dialogues of people who are no longer at the spaceship.

It is not very interactive, you can just look at booklet and bring the story to completion quickly. It can be played in a relaxing mode. It invites you to explore in each locations, but no obligation to do so. You get a sense of place and exploration of environment in an interesting way.

The player is a bystander, which makes it easy as things are linear. There are no branches to story, most of your controls are taken away. More about Tacoma later.

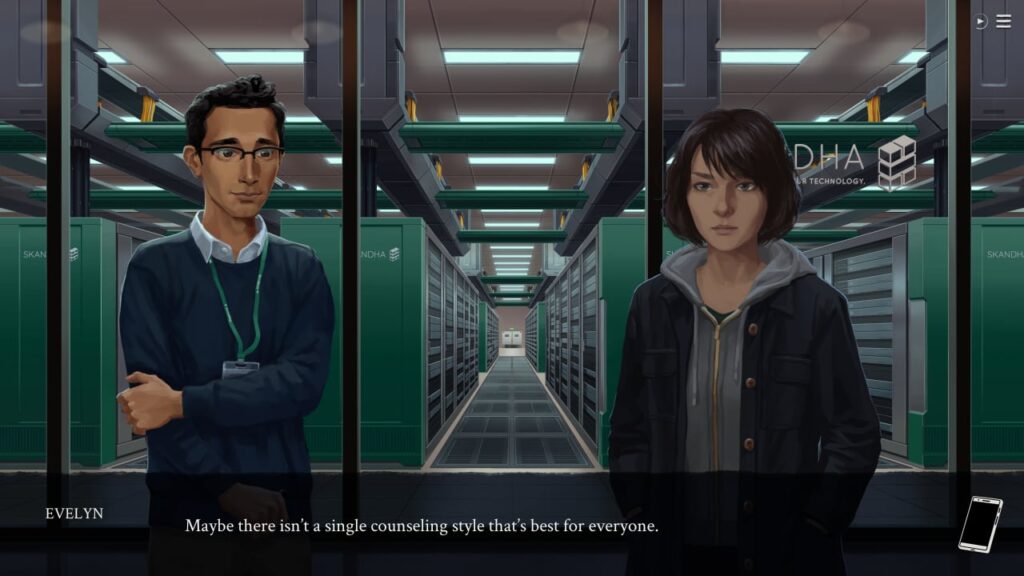

“Eliza” is a very different game. You play a therapist, in a visual novel type of game. This game has a lot of branches which you can explore one at a time. It is quite ‘wordy’, as it has lots of words, multiple paths, but all together it is a traditionally told story.

The writer of this games Mathew S Burns started from Twine and Elisa is in that spirit.

You have a lot of options, explore different branches, but Elisa actually offers you very little or no choice at all. You are a proxy for a therapist, a young woman called Evelyn, that was initially successful in the high-tech industry in Seattle, but burned out. You are helped by automated script that tells you as therapist what to tell a depressed client. You don’t have much effect on the game, but it is justified here as the story just takes you along.

Why the story offers little or no choice at all? The first patient is depressed and thinks nothing matters. Even if you are not interacting, the game has the tension in that we do get an interaction. It brings forward a central tension of the game – you express yourself with as much of limitation as you have to cope with but you are making a choice, even if forced to do it. It makes each of the choices your own, you are responsible for every advice. It reinforces hopelessness of the game set up and reveals limitations of therapy.

Responses to the patients are your only options. There are repeated lines, there is a lot about the weather and the therapists feels his own inadequacy to cope with the patient and to help him but only a few scrips on offer.

The patient knows that the therapist is human but aided by a robot AI Elisa. The patient wants to know if there are real humans up there and eventually is allowed to see it.

There is a certain confinement in the environment. There is also a need for the therapist to prescribe drugs. It is implied a kick-back deal is going on and the drug may not be actually necessary. It creates even more tension and shows conflicted motivation of empathy and the need to turn a buck.

Simon puts this exchanges in the context of his previous job in a call centre, where he was provided with a scrip of the conversation, and had to adhere to what the script was giving him. He had to sound empathetic in order to sell a higher tariff or subscription to a service.

Fake empathy in selling is a well know trick. Elisa picks up on this and our neediness leading to exploitation by crooks.

Today the replication of Call Centre scripts replacing human-human into human-machine-human makes modern communication process peculiar and uncomfortable.

In Elisa, there is a also a background of some how we will deal with the future stress of modern life, using virtual garden backdrops in our offices or bedrooms.

The game explores modern focuse on wellness, semi-religious routines, on Millennials taking it easy, being less full of ego lifestyle, all of those motivations drive Elise gameplay.

In the game, Techniques of therapy and methods of self-care are compared to religious practices. The game also notes that with our addictions to screens, the modern church is the server rooms which is powering apps. Simon shows the architectural similarity to temples of religious worship in cathedrals. In fact, Server rooms are modern cathedrals, supporting the collective worship of wellness on line.

Therapy program is trained by AI, it trains by itself but in Elisa it is given some God-like attributes, the sense of run-away machine-uber-alles ambience. The game is questioning how often we repeat routines, and scripted events of routine nature and implies it is not a bad thing. It may be what gives meaning to our lives.

There is a financial context to the game, as the app that supports the therapist, and it’s data crunching, is powered by a big financial organisations. It implies manipulation for gain, motivating force behind many modern oil snake therapies. It is a warning sign against giving yourself to seemingly God-like therapist who for commercial reasons does not have your best interests in mind.

Back to Tacoma – it is about hypercorporations, where tech giants have omni influence over people’s lives. An example of being surrounded by corportions is studying in Amazon University, where later you work for corporate to pay off your debts. This is countered by having automated set of tools at home as automated closet preparing your clothes every day, automation of everyday life dulling the pain of pointless existance.

In Tacoma there are no more people on the spaceship -something happens and the people are gone. They appear as holographic ghosts, we can observe their dialogues and explore the choices of other people, try to understand them. We can explore lives of people on the spaceship thru the artifacts, their belongings. AI of the ship acts like a therapist, like God – it hears your prayers and can act on them.

The game allows to explore the space inhabitants thru their objects. You can explore the differences between private and formal office space. We can see drinking issues hidden behind a smooth clean façade visible to others.

The game is based on environmental story telling (like System Shock, Half Life) using a strong cinematic experience. Interactivity with people is hard to simulate so the game is focusing on observations. The question is how much can you infer from objects and clothes.

As Tacoma shows, it is possible and emotionally moving.

Simon also shows Twine Story telling tool – demonstrates why story branches have to be very tight and have to come back together. Tacoma does that well and weaves a tight narrative with limited yet full-of-experience story branches. It can show both more personal and more formal facades, inspecting the tensions of different ‘faces’ we often present to different settings in real life. Memories of the spaceship are saved, for us all to explore, to examine the tragedy of the crew and what might have happened.

Both games explores the interesting notion of what it means to care. Listening, sensing, re-imagining people’s feelings and motivations is hard but rewarding experience which needs constant training to be good at it.

Journey – travel thru vast sand deserts with one other (ThatGameCompany) – reviewed by Ben Greenaway

Ben starts from explaining his issue with multiplayer games. His early experiences were in arcades, where you did not really play those games collaborative but competitively. It was all about scoreboard. The togetherness was being with the friends in the arcade, but not playing collaboratively – it was not an option.

Journey an artistic, artful travel adventure on journey from A to B but in the spin of Shadow of Colossus. There are no enemies, it just about exploring a mysterious, vast land. Ben was intrigued, as there was no words or customised avatars. It was to connect another stranger in a far part of the world and let you play with no words. Only one more stranger to meet.

“Having old friends, is the politics of last resort. Having new ones, is the first step for a change.” – the game’s motto attracted him to Journey. It is amazingly simple, with communication to the second player only in chirps. No lobbies here! You can fly up to the other player and re-charge your cap. Just take my money!

Journey was re-released 2019, in multiplayer format.

The second game, Sky – Children of the Light. A social indie adventure game by the same ThatGameCompany, it is beautiful, expertly framed, artists’ game.

The premise is you are alone in a magical kingdom using a cape that gives you the ability to fly. Everything is vast, there are seven kingdoms themed around a different stage of life.

Ben played with another person – the only means to communicate it makes a chirrup noise. There are no words. If you are playing with the friend, proximity with the friend recharges your jumping power. The interplay of the other person is expressed by a white dot, and you can fly to them and you can recharge your cape – this is the scope for your collaboration.

The game makes a strong play that you can form thru simple noises, and a strange connection is formed. You feel the need to stick together, it is quite strongly emotional.

Artistically the name is very minimalist, stripped back look but there is a lot of rules in Sky, unlike Journey. You can finish the level together and you can play together to 7 levels- you reward is entering the next level together. At the end of the game, all the way thru, when you finally make it to the name credits, then it shows you the tags of the name of people you encountered. People on forums commented that this made them emotional to realise they might have played with more than one person.

You don’t need to collaborate, as all tasks are there to be completed single handedly but they can be accomplished somewhat faster together. The multiplayer is not necessary but it helps, reflecting real life where you can join others to speed up your process. Sky has a number of lobbies like home lobby, level lobby. You can meet lots of people, but Ben questioned if it was worth so much learning, so much interface quirks to conquer, so many rules to memorise just to accomplish a simple task that can be done by yourself. The game is still in beta, so early days – sign up to give them feedback, particularly on what can be improved to focus on collaboration learning. For Ben Sky game has not enough of a goal and too many rules, too steep learning curve for not that much to accomplish together. Maybe collaboration games are better done in the restricted, minimalistic environments like Journey and not like rules-rich Sky. Or maybe the rewards needs to be shown early and often to encourage sticking with the learning of rules and complexity.